Note: The text includes words now considered to be dated in referring to Black Americans. We have preserved them, in most cases, to be consistent with the usage in J.R. Scurry’s time and his writing voice.

By the Rev. J.R. Scurry

On March 7, 1857 (just before the inauguration of James Buchanan as president), the Dred Scott decision was issued.

When it was announced that it was constitutional for a master to take his property (slave) anywhere he could find them, it made quite a stir among my people. We had some among us that had located here and had some property they stayed here and stood their chances. They belong to the underground and became a prey to those skulking hounds.

Our people were not alone in the cause. Every white man in the North protested the (Dred Scott) decision. It made no difference even if the white man in the north was a Democrat, he didn’t want to be made a target in trying to stop a runaway fugitive.

Some of the warmest friends we had in this town during the last days of slavery were white.

Many of southern birth were of great help to the Underground Railroad in this: that they left the South, brought a number of their slaves with them, set them free and gave then homes and employment. This class of Southerners also gave no aid in trying to catch a runaway negro.

If you want to know whether these sayings are true, ask Lawson Speaks concerning the Thomases, Ask John or Oliver Jones about the Brunners. And ask about the Quakers, too.

A chance encounter in the pit

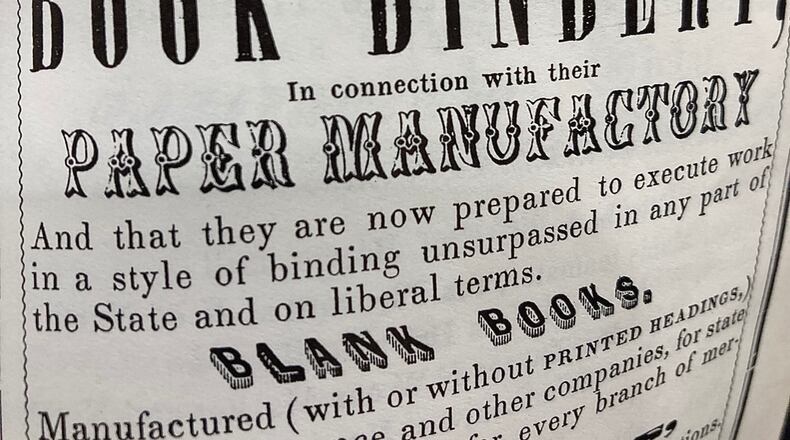

On the old race bank, midway between Main and Columbia street was a head gate to let the water out to the big paper mills of the Kills Bros., father and uncle to our well known Jack Kills, and a source of help for us.

Their mills formed one side of what was called the circus grounds, where we took two runaways down to see the elephants -- and see one they had to, especially after they heard us talking about the coming of Old Hannibal.

It turned into some risky business.

The fugitives were laying over, waiting for another comrade, and staying with Chris Hart’s mother, Aunt Betsy Hart, on Market Street. Two doors above that we had them hidden among some boxes and barrels in an old shanty in the rear of Starrett’s Shoe Store.

Pete Schutte, who works as a salesman for Nisley’s shoe store, Henry Honefanger and George Leuty came to my house to go and meet the circus as it came on Urbana Pike. The white boys going along with us didn’t know anything about it. We five colored fellows – including the two fugitives -- planned this.

The plan was that if anything looked suspicious on the road, we’d make for the halfway house between Urbana and Springfield and send the fugitives on their way. But it looked safe, so we all came back to town and carried enough water to sprinkle two miles of Main Street to hold down the dust.

In those days colored people and cheap white people sat in what was called the pit – a few boards spread on the grass or ground inside the tent. While sitting there that afternoon, one of the fugitives whispered to me he saw a man he’d seen on his master’s plantation. The man sat down right in the rear of us colored fellows.

I took a look when I got a chance and, behold, it was a man belonging to one of our own wealthy white families on High Street, who came home every summer to visit his people.

I knew him because I had lived with the family.

When he got up and passed right by me on the way to the spiked lemonade stand, I thought the jig was up. It was all I could do to keep them fugitives from making a hasty retreat.

Then it got worse. When he was coming back, he suddenly stopped. He recognized me, shook hands and asked in Southern phrase whether I had been a “good boy” since he saw me last.

Then he turned around and followed his companion to their seats. If he suspected anything, it was our business to sit there on the grass, watch every move that man made and not to let either of them get away from us.

Those fugitives didn’t see much of the show, I’m afraid. I said to Chris Hart, “If he’s on you, you go with one of the fugitives to Mill Run at Funk’s corner and I’ll go with the other to the paper mills.”

The show out and the crowd making for the door, we kept those men in sight, followed them to Fisher Street, then to John Shafner’s at Main and Market streets, where they went to get a drink. The fugitives went on with us to Aunt Betsy’s.

The next night, along with six others, they left this station for Urbana, Abe Nutter running the train through. In several days, the brother arrived and was sent past the halfway house on the same route.

All got through safe, but I felt worse in those two hours at the circus than if the chasers were on our path.

Part I: Sunday, Feb. 7 - The Underground Railroad: The escape

Part II: Sunday, Feb. 14 - The Underground Railroad: The dangers of cherry bounce

Part III: A near miss in the cheap seats.

Next Sunday: Aunt Sukey, “Bat” Shavers and the rest

About the Author