Lamar Kilgore remembers it as an awakening moment for him that’s connected with what he hopes will be an awakening moment for the nation.

The awakening part does not appear in the Springfield Daily News report of Oct. 30, 1946. But the sports section does report the essentials of what happened at Evans Stadium the day before.

The Purple of Springfield’s Schaefer Junior High had been upset 7-0, suffering what would be the lone loss of a 5-1 city championship season sealed in the final game when the Purple schooled a traditionally strong Keifer Junior High team 27-0.

The extent of the suffering involved in that year’s sole loss plays a critical element in Kilgore’s awakening, which I’ll return to momentarily.

That 1946 season, game and moment came to Kilgore’s mind at his home in the Philadelphia suburb of Malvern, Pennsylvania, not long ago when he came across three pictures of the sort often celebrated by members of the revived Golden Era Wildcats. That’s the group of people who gather quarterly now to remember what they remember as the “golden era” of their alma mater, Springfield High.

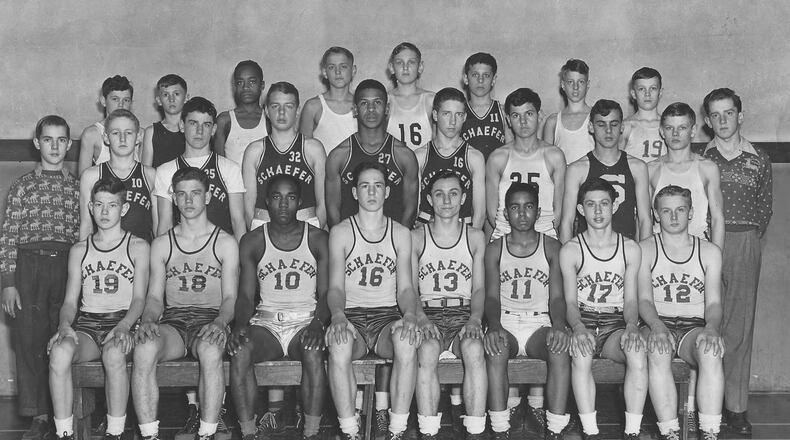

As they would remark – and Kilgore says – the black-and-white photos are in amazingly good condition after the passage of 75 years. In sharp focus, they show the mostly smiling and youthfully fresh faces of the members of the Purple’s football, basketball and track teams, all of which were city champions in the very competitive junior high league of the era.

Schaefer’s winning ways in all three sports that school year prompted Kilgore, whom I’ve written about before, to ask me a question: T. How many other junior high schools swept the city championships. Any?

I habitually refuse to answer such questions, knowing full well the tempestuous teapots created by anything short of the definite answer to the question in a matter of sports. It’s better to let those at the Golden Era Wildcats bandy about that over pizza than a reporter — especially a hatchling from that state up north — to hazard a guess.

I would hazard to guess that discussions among the Golden Era crowd – and even local sports fans who weren’t around then – would touch on the players on those teams, particularly given that Kilgore was on the 1950 Wildcats State Championship basketball team.

In his email, Kilgore provided the answer in a sentence with two and/ors: “I can identify no less than eight guys who won athletic scholarships to college and/or were later inducted into the SHS and/or athletic halls of fame.”

In addition to Kilgore, who went on to play basketball and golf at Wittenberg University, they are: Bob Bronston, Al Sanders and Joe Powers, all of Miami of Ohio; Bob Englefield, Auburn; Don Morris, Vanderbilt; Bill Slagle, Ohio State; Jack Sallee, University of Dayton All-America; and Dick Shatto, who went to the University of Kentucky and then stardom with the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League.

Although Kilgore used the first name “Al” to identify Sanders in this list of Schaefer athletes, Sanders appears as “Albert” in Kilgore’s reflection on his moment of awakening in October of 1946.

“The Schaefer team had moments before heard the final whistle of their last minute loss,” Kilgore writes. “With heads hanging and cleats clattering, they trudged down the concrete ramp to where they all, save Albert, slumped on the benches.”

“Hands concealed muffled sobs,” Kilgore recalls, with the exception of Albert, who always had a different air about him.

“With arms folded and legs crossed in nonchalance, Albert stood apart,” as he often had.

Teammates’ attempts to tag him with a nickname befitting his size – “Moose” or “Big Al” – repeatedly got the same response: “My name is Albert.”

And Kilgore remembers that as all his other teammates were shocked to the core, Albert, who is Black, said softly — and almost to himself — “Losing a football game ain’t no reason to cry.”

There is much talk these days about the need for people to have “difficult conversations” about race, something that largely seems like a non-starter to me for an activity that requires voluntary participation. Difficult conversations are difficult enough. Difficult conversations about race, however necessary, are more difficult to a quantum degree. Volunteers, I presume, are scarce.

In that context, Kilgore’s reflection can be seen as a conversation with himself, jogged by a comment made the fall before Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball and what Kilgore’s reflection describes as the “ ‘Jackie, Oh, Jackie’ delirium in the colored-only upper tier of Cincinnati’s Crosley Field.”

The segregated seating there reflected the balcony-only seating for Blacks in Springfield and most other movie theaters of the time.

Kilgore allows that although Springfield “was not completely segregated, the unseen lines of social and economic separation were very solidly drawn.” (Today, it’s called red-lining.)

After the Springfield High School Championship year, Kilgore went on to Wittenberg, then law school in Philadelphia, where he began receiving an elementary education in race. Beginning in 1955, he lived for three years “in a walkup apartment jowl-to-cheek with the west Philadelphia ghetto.”

He also “did a full year tour as an on-street insurance claims adjuster in the south Philadelphia’s ghetto” and was a volunteer public defender, which had him interviewing prisoners “all Black, who, lacking bail bond were detained on mostly non-violent criminal indictments in notorious Holmesburg prison.”

Then came the race riots and assassinations of the 1960s – and the more recent events that have left himself “confounded by the numbers of those who deny the existence of white privilege, systemic racism and the injustice which defines what it is to be Black in America.”

Among them, he says are the “otherwise nice people” with whom he regularly plays golf, a sport he says has caused him to walk a hundred miles a year for the past 75 years and contributes to his current good health.

“If I raise the subject” on the course,” Kilgore says, “it doesn’t work,” I think because no one wants to volunteer to participate.

But he has developed a successful technique that might be akin to a good fade shot off the tee.

“I’ve discovered that if I wear a Black Lives Matter logo and they ask me about it, “then they listen, as a matter of courtesy.” Recently, he said, he logged on and found an email from someone who had asked about his BLM swag and wanted to continue the conversation.

The payoff wasn’t profound. But he at least had done something – something he might have done had Albert Sanders not said anything in his earshot 75 years ago about what is and isn’t worth crying over.