As a lawyer would, he framed the issue in terms of a proposition: “That all men are created equal.”

It may be the greatest irony not just of our history but all history that those words had been written by a slave owner from Virginia, Thomas Jefferson. The irony gets steelier if we remember that, after the international slave trade was outlawed, Virginia answered the heightened demand for slave labor in the South – and the profits such a demand might earn — by breeding people much as Kentucky bred horses.

Although it deserves its mythic status, 1,000 readings have led me to think of the Gettysburg Address as Lincoln’s stump speech for the Emancipation Proclamation, the lynchpin of his strategy to win the war by elevating its goal from saving the union to ending slavery and saving democracy itself.

Because slavery was constitutional, Lincoln justified the constitutionality of his proclamation by arguing he had the authority to temporarily end slavery in the Southern states in his role as commander and chief of the United States armed forces in a time of revolt. That authority was nowhere written down and never tested in court.

The Emancipation Proclamation did have practical results for the war. It prevented Great Britain, which had banned the international slave trade, from officially recognizing the slave-holding South as an independent nation. In addition, as Union armies advanced and slaves were freed, the proclamation both deprived the South of its economy’s labor force and bolstered the ranks of the Union army with freedmen fighting in the cause of their own freedom.

(The need for more recruits was underscored 10 days after the Battle of Gettysburg, when Union troops were sent to New York to quell against the federal draft in which Blacks were indiscriminately murdered.)

Lincoln himself avowed — detractors may prefer the word “admitted” — that, as a practical matter, it would have been impossible to save and maintain the nation without destroying slavery. Years before the war started or anyone imagined someone from backwoods Illinois might be president, he had proclaimed that slavery was dividing the national house the founders had framed in a way that would lead to its collapse.

There is political genius in Lincoln’s argument that the best way to save the nation was to bolster support for it by joining the sources of its moral and structural integrity as a carpenter would join wood.

And for the motivating force to strengthen the bond, he reached back fourscore and seven years beyond the United States Constitution to the Declaration of Independence. From it. he plucked those six words now grafted to the heart of the American experiment.

In our subsequent squabbles over what “all men created equal” means, we have overlooked a radical fact: That for a species which so regularly seems unable to recognize even one another’s humanity, equality is a revolutionary goal.

The most hotly debated question in the current unholy war in the Holy Land centers on accusations from both sides that the other’s purpose is to carry out the extremist’s most extreme form of unequal treatment: genocide.

But north of the brain stem in which our baser instincts dwell resides the guiding star of conscience. As the North Star led people escaping slavery on the path to freedom, Lincoln argued the dream of equality could take us on a better path.

And he believed that for the larger human family, the path offered by American democracy represented “the last, best hope of earth.”

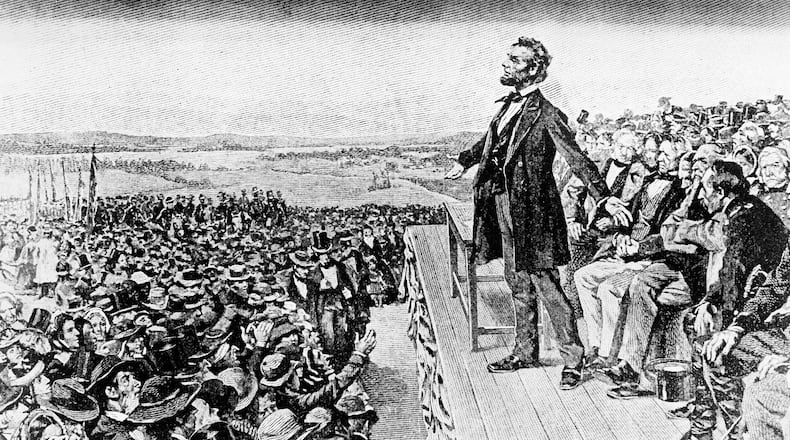

To those who had traveled to Gettysburg to dedicate the cemetery, he said that the brave men who struggled there had had already done so and that the job had been far above the pay grade of those who gathered that day, anyway. His words were “far beyond our poor power to add or detract.” He then told them they instead should “be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us” and “that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that that cause for which gave the last full measure devotion.”

In a rallying cry to win the war for freedom, he said it was imperative that “we here highly resolve (pause) that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God shall have a new birth of freedom, and “that government of the people, by the people, for the people — shall NOT perish from the earth.”

I’ll finish with a few words about “a new birth of freedom.”

In mathematics, equality seems simple, the balancing of the two things on either side of the symbol we use to represent it. Like freedom and justice, it is and will always be an aspirational word. But its ability to inspire deeds and not just words has brought us closer to the aspiration.

In alluding to the end of slavery as “a new birth of freedom” — as a step toward equality — Lincoln captured what it is like when some closer proximity of freedom is born into this world. As with women’s suffrage and gay rights, the birth does not mean the immediate full development of equality, a harsh reality that led the lyricist of “We Shall Overcome” to finish the most sung refrain in American Civil Right history with the words “some day.”

The Gettysburg Address reminds us of two things:

That successive rebirths of freedom will always be “the great task remaining before us.”

That Americans who undertake the great work can find inspiration by reaching back, as Lincoln did, to words spoken when it was conceived.

About the Author