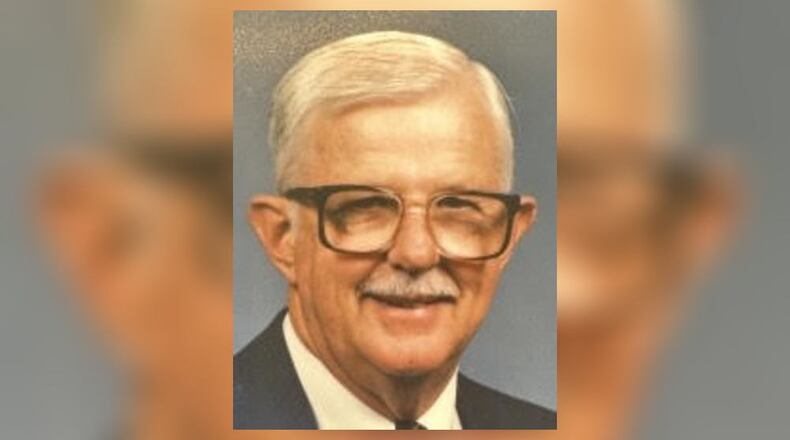

From, 1963-85, Dale McDonald compiled a combined record of 193-131-3 as varsity football and basketball coach and filled that niche in memorable enough fashion that students and players of that era are creating a memorial to him.

Downwind from a recent 50th reunion, a core of alumni from the Shawnee High School Class of ‘72 is finishing a fundraising campaign for a plaque to honor McDonald, who died 13 months ago at 92. With $3,300 in the bank, the group hopes to up the total to $5,500 by month’s end.

Former players allow that McDonald occasionally shot a withering look across the field and periodically flung his clipboard like a Frisbee. But they agree that he was, at bottom, the steady, calm person their classmate Lisa McDonough Coleman remembers watching while playing at her friend’s house as a 9-year-old.

“A more relaxed man mowing his yard you could not find. That kind of what his approach was with everything: ‘All in good time, I’ve got it under control, and we’re just going to take care of this thing.’ "

“He was genuinely friendly (and) kind of like a father figure to everybody,” said Coleman’s classmate Rusty Bartley, ‘72. Bartley said, “He had a personal way of connecting” that won Bartley oved as a high school sophomore.

Although he would grow considerably in adolescence, Bartley said, “I came into Shawnee as a guy of very small size, and (thought) I was not going to play much football. But he also entered in sophomore year with a hope kindled by Reid School football coach Jeff Dorn that he might be a kicker for the football team.

“Dale McDonald took as much interest in me wanting to do that” as he did in other players with more obvious football potential, Bartley said.

“My story with him is both on the field and off the field,” said teammate and classmate Brett Smith.

“He coached us according to what we needed at that time – from a hug to a kick in rear.”

It was the former McDonald provided the day a crestfallen Smith came out of the guidance office after being told he shouldn’t go to college. It was a body blow to the son of two college graduates who had the same expectation for him.

“He said, ‘Don’t worry about that,’ ” Smith recalled. “’If you want to get into college, we’ll get you in college.’” Then he did.

Ted Brunner, ‘71, said it was the “kick in the rear” version of McDonald who walked up to the lunch line one day with a stiff jab of a sentence: “Get your geometry grade up.”

That Brunner hadn’t been putting in much effort was evident in his grade’s rising from a D- to an A. All these years later, he is among players who appreciate the time and effort McDonald invested in them.

“My senior year, I was taken to Capital, Muskingum, Eastern Kentucky and Heidelberg” to see football games and tour campuses. “Consider this is a football coach” who had coached the night before and was getting on Saturday morning to take his players college shopping, Brunner said.

“That’s why I ended up at Heidelberg,” then coached by Pete Reisen, who graduated from Wittenberg University in 1951, the year before McDonald. Other Shawnee graduates would follow from the 1972 team that first watched, then helped, McDonald post a 22-3-1 record.

“Ted comes back (from Otterbein), and he could have been a salesperson,” said Bartley, who also played at Heidelberg with Brunner, Smith and Jerry McDonald, ‘73, a Braves quarterback and the coach’s son. (Dan Brown, Greg Kittles and Kurt Smith from the same era joined them on the Tiffin, Ohio, campus.)

Bruce Schibler, ‘72, would meet them there on game days.

“On those Saturday visits to colleges, we also went to Wooster, where I decided I was going, That’s the first time I ever saw Wooster.”

Because the two schools shared schedules, former Shawnee teammates lined up against one another for four years, the mention of which led to Brunner’s pre-emptive defense of a play that landed Schibler on the Heidelberg sidelines.

“I blocked Bruce. It was my job. I didn’t hold him.”

When Schibler shot back, “I didn’t get there (to make a tackle) because he tackled me,” Brunner fell back on what journalists call a non-denial denial: “Excuse me, was there a penalty on the play?”

During those four years, McDonald and his wife, Hattie, attended the games, the last three years to watch son Jerry share the field with other Shawnee players.

Said Schibler, “I got to thinking: When he would come to a Heidelberg-Wooster game, I don’t know if there’s many high school coaches that could go to a game and have more kids on the field at the same time.”

On the weekends of those football seasons, Bartley said, the relationship between the players and their former coach changed.

“We went from Coach (and Mrs.) McDonald to Dale and Hattie McDonald. That transition during those years was really special.”

“After we graduated, I was inducted into the athletic hall of fame at Heidelberg, (which) would not have happened without his involvement in my life.”

Nor, he added, would have the 30-plus year careers in coaching and education of all four players quoted to this point. Schibler, who coached at Kenton Ridge, had the additional pleasure of McDonald, by then retired from Shawnee, as an assistant his staff.

At McDonald’s funeral service last January, Lisa Coleman heard a tribute of another sort from the older of two brothers who lived down the road from the McDonalds and had lost their father as a boy.

He was in tears when he told her: “That man was like a father to me when I didn’t have anybody.”

Jerry McDonald said he, his two brothers and their sister “always had access” to their father and, despite the spotlight on them as a coach’s children “wouldn’t have traded it for the world.”

He conceded there “might have been pressure” on him when he was the starting quarterback for his father’s teams, but said “I don’t think he did much at practices” that would raise an eyebrow.

“I do remember,” he said, occasional outbursts from the McDonald basement on the days his dad reviewed game films.

Both in appearance and resume, Jerry is a chip off his father’s block. After Heidelberg, he taught and coached high school for eight years before returning to the Tiffin campus, where he coached football for 35 years – the latter ones with his parents in the stands.

“After games he’d tell me things I didn’t want to hear,” the son said, “but he was a great.”

As was his mother, who her son said filled the niche of a coach’s wife and the mother of a houseful of athletes just as fully as her husband did his.

“She was the hub of the wheel who got us where we were supposed to be when we were supposed to be there;” always had “her heart out there on the field and the floor with us”; and managed to tolerate the unkind remarks of grandstand coaches while living and dying with her husband’s teams.

“She was big on sportsmanship,” her son added, “and reminded you” of failures to live up to it.

A year now after his father’s loss, McDonald said he and his family are “deeply touched to have student athletes this far along in our lives take the time to recognize him.”

A measure of the depth their appreciation?

“Every time we mention this project to my mom, she just lets out a sigh.”

How to donate:

Donations to the Dale McDonald Memorial Fund can be made by sending a check written to the fund at and sending it to 17400 Lockbourne Eastern Rd., Ashville, OH 43103; via credit card by calling Brett Smith 614-736-0038; or by directing a Zelle electronic payment to dmcdonaldmemorial@gmail.com. For more information call Smith at the above number.

About the Author