Last week, it was worth a check of this newspaper.

Because just a couple inches from the beaming portrait of late Horace Leslie “Newt” Hansell were two sentences that, together, made me laugh out loud:

“(Hansell) “claimed his father gave him the nickname ‘Newt’ after his mule.

“The mule was never consulted.”

It seemed straight from the mouths not only of Hansell, who was 92 when he died May 8, but of his spiritual kin Waldorf and Statler, the two clever old guys who trade insults in the balcony of the Muppets theater.

I give the family high marks for slipping the lines in near the top of the obituary, right after a sober detail Hansell was proud of: being a direct descendant of Springfield founder James Demint.

Because of the journalist in me I had to ask Jeff, one of four Hansell sons, a little more about the mule, coming up with this scoop: “His father liked the mule.”

Whether Zeke Hansell also got a nickname from a mule is lost to history. What is known is that the four-legged Newt helped him to haul things in wagons and carts while he made a living out of his home in the Limecrest area at a time when residents there weren’t privy to indoor plumbing.

MORE FROM TOM STAFFORD: Coronavirus a truly social disease

For most people, Hansell, the two-legged Newt and the fifth child of Zeke and Mary Demint Hansell, is associated with another form transportation: the railroad.

Born Jan. 5, 1931, he was tagged the New York Central Railroad’s “boy dispatcher” of Springfield at age 19, a couple of years after his older brother, Truman (nickname Hank, of course), landed him a part-time job at the railroad.

A story of Hansell’s lifelong inability to sit still survives from his early railroad days as an assistant dispatcher and freight agent stationed in Mechanicsburg. Rex Cochran, a rail retiree from Cincinnati, recalls being sent to fill in for Hansell, who had a week off.

The he found evidence said that during slow times on the job, Hansell would throw a hatchet at a post in the freight area of the depot.

“I think he was pretty good (because) the post had a lot of hits on it. I was 19, and he was not much older.”

As he continued his career, Hansell’s job, which was like being an air traffic controller for trains, “involved a lot of responsibility,” said son Mark Hansell, of Columbus. “And there were times when that responsibility got to him.”

Helping him manage it was Barbara Louise Elliott, whom Hansell’s obit describes as “a good match” for him, having “an equally gregarious and congenial nature.”

Marrying in 1952, they had five children and presided over a home “whose dinner table welcome family, friends and complete strangers who were constantly dropping in,” the notice said.

Among them were a string of international students from the Lions Club’s Youth for Understanding program – students who bolstered the size of the family.

Jeff Hansell says playing host to students illustrates his father’s penchant for looking after people in the way he always looked after the signal maintainers, track gangs and others exposed to danger along the tracks.

MORE FROM TOM STAFFORD: Wedding vows need updating to help couples survive quarantine together

When Jeff was bouncing around after high school and his dad found him a job as a signal maintainer’s assistant, he came across a story of how his father looked after a Vietnam War sniper working for the railroad and known to everyone as “Crazy Don.”

After Hansell had been transferred from Springfield to the NYC’s dispatching center in Cincinnati, he heard by way of portable radio that Crazy Don had an accident with a New York Central truck near Middletown on a night when the latter may or may not have been drinking.

“After he got off work,” Jeff said, Hansell “drove up, found where Don was, got him to the doctor, and got his truck back to Springfield.”

“He saved my life and my job,” the combat veteran told Jeff.

The hosting of foreign students also may speak to Hansell’s belief in education, one that may be been related to his having been offered a scholarship to Harvard after graduating from Greenon High School but not being able to attend because of related expenses.

Stories survive of him reading the newspaper while taking it out to the trash.

“Dad inhaled books the way people breathe air – anything and everything. And then years later, he would read them again.”

A particular fan of Pulitzer and Nobel Prize-winning author Saul Bellow, Hansell gave Jeff two pieces of advice as he worked his way through college. The first was “learn how to learn, because you’ll being doing that for the rest of your life.” The second was “ learn how to listen, because you’ve got to know how other people are thinking and feeling.”

Jeff links that to his father having to interpret what others along the tracks – all from a variety of walks of life — were telling him while he tried to manage hazardous situations. Because interpreting at those moments could involve matters of life and death.

Son Mark said that not all was serious on the railroad, though. While his father and others “took their jobs seriously, they took their playing seriously, too.”

Particularly while playing pranks.

MORE FROM TOM STAFFORD: A stimulus response? Join the 1200 Club

One was hatched while Hansell was working in Columbus in the 1970s and one of the others at the dispatching center was particularly proud of the mileage his Volkswagen Beetle was getting during commutes to work.

Over a period of weeks, Hansell and the others went to the isolated employee parking lot to at first add, then siphon gasoline from the car. The former caused its owner to crow of mileage of up to 75 miles to the gallon. It was after the siphoning nearly led to an altercation between the driver and his mechanic that the ruse was made public.

As much as he enjoyed his 42 years on the job, “when he retired, he was done,” Mark said.

But he was still unable to sit still, which became obvious when he returned from what was supposed to be a 10-day vacation with his wife and other couples in Florida, after three days.

Soon, Mark said, “he decided he was an artist.”

Although their father’s interest in chalk drawings, sketches, painting and even sculpture pleased his family members, Mark said, it also left them wondering “Where did this come from?”

The answer was from a perhaps mule-like quality in Hansell.

“He just did what he liked to do,” Mark said.

During his art phase, Hansell hung around the Springfield Museum of Art enough that Mark Chepp, its former director, hired him to work the front desk – and got to know Hansell and his art.

Although largely self-taught, “some of the images he came up with were semi-surreal or semi-outsider,” Chepp said. He himself owns a flat sculpture with two eyeballs on it Hansell titled “The eyes have it.”

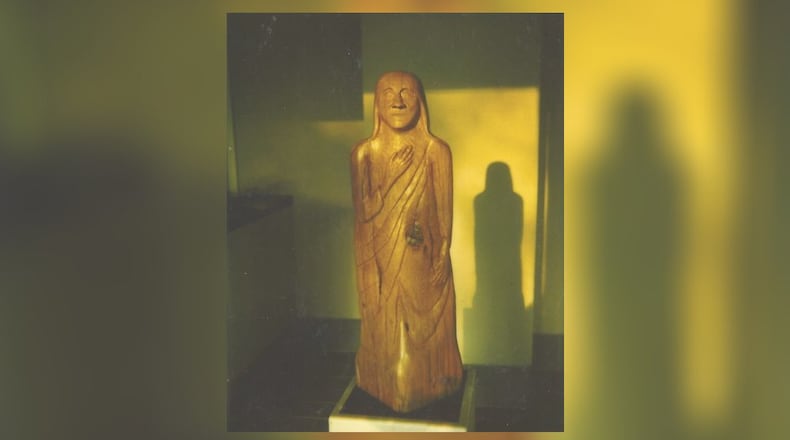

One of Hansell’s favorite piece started with a shape that caught Hansell’s fancy, “and when he started to manipulate it, in his eyes, it became Mother Theresa,” Chepp said.

And although Hansell wanted it in the members’ show, he didn’t really want to sell I the sculpture, which was a condition of its being in the show.

When Chepp advised Hansell to price it not to sell, the artist appears to have gone into semi-surreal or semi-outsider mode. When Chepp next saw the sculpture in the museum’s front window, it was priced at $30,000.

Like four or perhaps all five of his sisters before him, Hansell fell victim to Alzheimer’s disease. That led to suffering that hangs when Mark says “He’s been gone a long time.” But it also proved another instance in which his father’s caring nature shone.

As soon as the diagnosis was confirmed, Hansell signed all the necessary papers regarding family finances. So, when the family visited the Alzheimer’s Association to get advice, a brief serious of questions led the person helping them to say – in a not unfriendly manner — “Why are you here?”

Because no story about Newt Hansell should end on a sad note, here is a final recollection from son, Jeff.

When his father was in the throes of his art work, he went to visit Jeff in Boulder, Colo., where Jeff arranged for art shows in “a couple of hipster coffee houses.”

After having to stop his Dad from giving the pieces away to people who said they liked them, a piece was sold. Brimming with satisfaction, Hansell announced the results just in from a comparison of the lifetime sales of two artists.

“Me, 1, van Gogh, nothing.”

The funny thing is, just as his Dad had liked his mule Newt, Hansell had pretty much liked van Gogh.

(Streamed services were held for Hansell Thursday. To enjoy the family’s lovely obituary on line, use the search words Horace Hansell Springfield Legacy.)

About the Author