Some of the online criticisms focused on Ms. Chess’ observation that Fairborn has a history as a “sundown town,” a place where Black people could work during the day, but under an informal policy, needed to be out of the town by the time the sun went down. Several online commentators asked Ms. Chess to provide proof of her claim. With a tone of disbelief one said: “I’m waiting….”

In the first half of the 19th century, Ohio was threaded with Underground Railroad routes, as enslaved freedom seekers from Virginia, Kentucky, or even farther south traveled through our state seeking to live as free people here, or continued on their way to guaranteed freedom in Canada. The central characters in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin brought this harrowing journey to life for many Americans, leading to a growth in anti-slavery sentiments in the north in the decade before the Civil War. We are rightly proud of this history of our state as a refuge and advocate for freedom seekers.

But there is a parallel history that the outcry over Ms. Chess’s comments indicates we need to understand more clearly. That is the history of anti-Blackness in our state. Ohio became a state in 1803. The next year Black Codes legislation was passed by the Ohio General Assembly requiring Black people seeking to live in Ohio to show certificates confirming their free status and registration with the county clerk.

An 1807 expansion of the Black Codes prohibited Black children from attending public schools, required Black people to post a $500 bond (which was more than the average annual household income at that time) guaranteed by two white men, and prohibited the testimony of Black people in court proceedings. Black people were not welcome in Ohio because of the belief adopted by some in northern states, that they were inferior, a perspective that had been used to justify Black enslavement. Some Ohioans were against slavery and were also against the presence of Black people in the state.

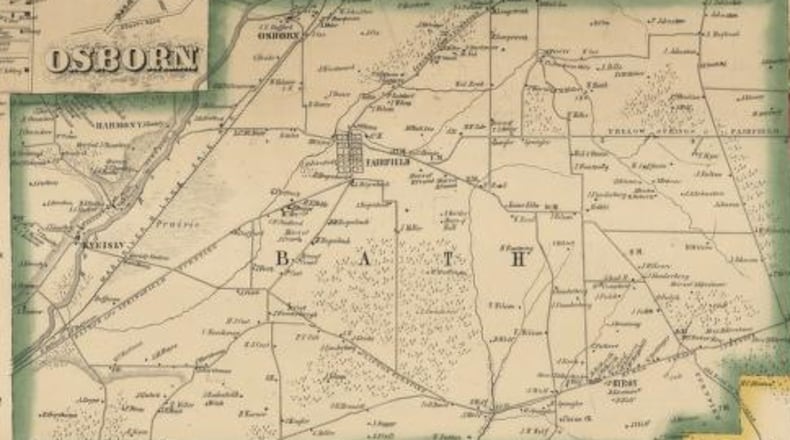

In Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, author James W. Loewen noted that “beginning in about 1890 and continuing until 1968, [W]hite Americans established thousands of towns across the United States for whites.” Substantial evidence indicates that as early as the 1860s, the town that is now Fairborn was one of these sundown towns. Fairborn is the result of a 1950 merger between the towns of Fairfield and Osborn.

After the 1913 Miami Valley flood, construction of an earthen dam led to the relocation of Osborn to an area east of Fairfield. The original plats for Fairfield’s one hundred and fifty lots, in Bath Township, Greene County were recorded in the 1810s. Regarding Fairborn, the 1840 book, Condition of the Free People of Color in the United States of America explained that in 1838, “the town’s overseer of the poor had issued a notice to all “black or mulatto persons” residing in Fairfield, to comply with the requisitions of the act of 1807 within twenty days, or the law would be enforced against them.” This policy was very effective in Fairfield and Bath Township. The Census records indicate four Black residents in Bath Township in 1840, six in 1850, and one in 1860. The Christian Recorder newspaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, reported on an 1867 Thanksgiving Day speech given in Fairfield. Because the town “had a reputation of having been exceedingly hostile to the presence of Black people,” there was surprise that B.K. Sampson, “a young black orator in the community,” had been invited to be the speaker.

Census records indicate that between 1880 and 1920 no Black people lived in Fairfield or Bath Twp. Forty-three lived at Wright Field in 1930, but in 1940 again there were no Black residents. In 1950 there were two Black people residing in the merged city of Fairborn. The evidence regarding the sundown town status of Fairborn, that the online commentator is waiting for, is not just in these statistics.

While southern states had explicit segregation laws on their books from the 1880s until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, northern communities adopted segregation practices, that were informal, but as strict as southern segregation laws in some communities, while more flexible in others. Black people living in these communities, or nearby, shared this information verbally from generation to generation, since their safety depended on it. Many White residents were oblivious to the practice, assuming that Black people preferred to live elsewhere.

This is the evidence that Ms. Chess was sharing with the students at Paul Quinn College in October, and for which her online critic claimed to be waiting. Like most college alumni returning to speak to current students, Ms. Chess seems to have wanted to share with the students the challenges she had overcome to succeed, conveying to them that they will face challenges that they too can overcome. Her observations regarding Fairborn’s sundown town heritage, match what I have learned interviewing Black elders through WYSO’s Civil Rights Oral History project.

They note that while Wright Patterson Air Force Base was and is an important source of employment for Black people in the Miami Valley, until the 1970s they could not live in Fairborn, the community surrounding the base.

While this information may surprise some people unaware of this history, rather than denying it or reacting with defensiveness and hostility toward Ms. Chess, who was recently censured by Fairborn City Council over her speech, I encourage them to reflect on how Fairborn can continue to eliminate any vestiges of this history of inequality that was supported for so long by some Fairborn residents.

A native of Toledo, Kevin McGruder, Ph.D. is an associate professor of History at Antioch College; he is the author of Race and Real Estate: Conflict and Cooperation in Harlem, 1890-1920 (Columbia University Press, 2015) and producer of “Loud as the Rolling Sea,” (https://www.wyso.org/loud-as-the-rolling-sea) a podcast series based on WYSO Civil Rights Oral History interviews.