“Pete gets Ty-breaker,” read the banner headline.

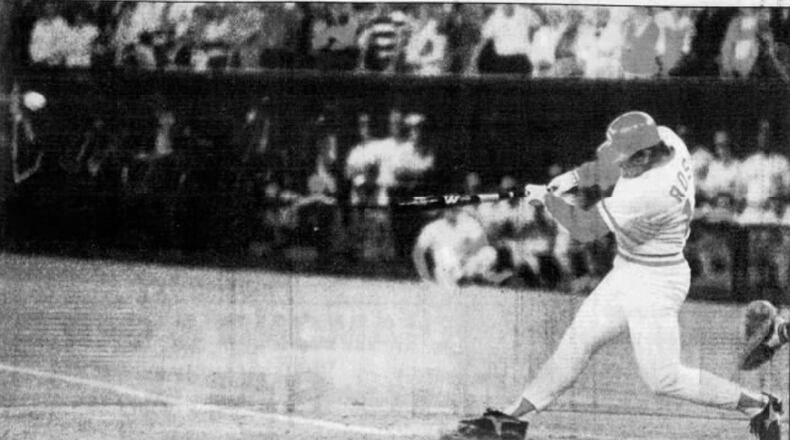

John Erickson, Marc Katz, Dave Long and Paul Meyer all had stories about Rose in the newspaper the next day. Staff photographer Bill Waugh captured the ball coming off Rose’s bat, and the photo ran on the front page. Skip Peterson, Ty Greenlees and Charles Steinbrunner also photographed the game.

Inside the paper, a special section prepared mostly in advance celebrated Rose’s achievement. One of the features in that section looked back on each of his milestone hits leading up to No. 4,192, the hit that pushed him past Ty Cobb in the record book.

Here are excerpts from that Sept. 12, 1985, story:

NO. 1

Bob Friend was in his 12th season as a National League pitcher with 153 victories to his credit when he faced the Cincinnati Reds on April 13, 1963.

The Pittsburgh Pirate right-hander was to get his name in the record book in an odd and unwanted statistic before his 12-4 victory was finished.

“I also didn’t know I was going to become a trivia item, either,” Friend said from his office in a major Pittsburgh insurance concern.

The curious and forgotten statistic was that four balks were called on him.

The trivia bit that will live as long as baseball is played is that he was the pitcher who gave up Pete Rose’s first major league hit.

“Sure, I remember it very well,” the Purdue graduate said, “and not just because of Rose breaking Cobb’s record.

“There had been a lot of talk in spring training about this Cincinnati rookie who ran to first base on a base on balls. People called him a hot dog and we opened the season in Cincinnati on a Monday and came back for a weekend series, which is where I faced him.

“We had seen him drop the bat and run to first base when he drew a walk off Earl Francis in the opener. He was hitting left-handed off me, of course, and our report said his best power and best stroke was the low ball inside. Most left-handed hitters are that way. I was keeping the ball away from him when he sliced the triple to left. It wasn’t easy to hit a triple in Crosley Field. But he took off and never hesitated.

“I had a feeling he was going to be a tough out. You could tell his intensity was real. He stood in there (in the batter’s box) as if he had been around for 10 years. I don’t know about other teams, but it didn’t take long for him to convince the Pirates he was more than a hot dog only pitched against him the first three years of his career and he hadn’t established his greatness at that point. I’ve always enjoyed watching him after my playing days were over. He was one of those batters who usually got a piece of the ball, capitalized on the pitcher’s mistakes and didn’t make too many of his own.”

“The thing about Pete that is truly amazing to me is that he has played so long and so hard without losing time to any serious injury. He’s had to take great care of himself and he had a great body to start. What he’s doing is a great thing for baseball. He’s a great example for kids. A lot of media people are calling me and I really am happy to be involved in a very small way in the celebration.

“The Pirates had me present him with a bouquet of roses on Pete Rose Night on his last visit to Pittsburgh. I have nothing but admiration for him.”

NO. 1,000

Even in 1968, Dick Selma could tell Pete Rose was headed for some records, but the pitcher who allowed Rose’s 1,000th hit that summer doesn’t think the next generation of baseball players will produce any record-breakers of Rose’s magnitude.

“I don’t think records are going to be broken any longer,” Selma said in a telephone conversation from his Fresno, Calif., home. “I mean longevity records, milestone records. With the money today, a player won’t be playing 20 years because he doesn’t have to.

“And what owner is going to pay a player a million a year for 20 years? It isn’t going to happen. What player is going to stay around to break Hank Aaron’s record? I think longevity records are gone. Nolan Ryan’s (4,000 strikeout) record? Kiss it goodbye.”

Rose reached 1,000 with an infield single in the third off the Mets’ Selma in a 7-6 Cincinnati victory at Crosley Field on June 26, 1968.

Entering the game, Selma was 7-2, but he finished the season at 9-10, although his ERA stayed below 3.00 all season. In this game, Selma lasted but 4½ innings, allowing eight hits and six runs.

“I don’t remember the hit,” Selma said. “But I know he got it off me. I read about it in the paper the next day. It was nice, but I was in Pittsburgh (with the Phillies) when (Roberto) Clemente got his 3,000th hit. I always thought if anybody was going break Ty Cobb’s record, it would be a guy like Rod Carew or Pete Rose. I didn’t think they’d break it, but if anybody did, it would be a singles hitter.”

There was some kidding of Rose in the Reds’ clubhouse when the game was over.

Vada Pinson, Cincinnati’s fine center fielder, injured his leg in the game, and had to use a crutch as he walked over to Rose’s locker.

“Son, let me tell you about my 999th and 1,000th career hits,” Pinson said. “My 999th was an inside-the-park homer and my 1,000th hit was a homer over the wall.”

“I get the point,” Rose said. “Mine wasn’t much of a hit. But when, in a few years, I’m standing here after Johnny Bench gets his 1,000th hit and I’m telling writers about my 1,000th hit, I won’t be on crutches, old man.”

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

NO. 2,000

Lots of players get 2,000 hits and lots of pitchers give them up, so it’s understandable why Ron Bryant’s first reaction to recalling Pete Rose’s 2,000th hit was a bit fuzzy.

“I know I gave it up, but I don’t remember much about it.” said Bryant, a left-hander who pitched for the San Francisco Giants on that June 19, 1973, day and now operates service stations in South Lake Tahoe, Nev.

There was a pause on the telephone, then, “He hit a ground ball up the middle,” Bryant said, and was right.

The hit came in the sixth inning of a 4-0 victory by the Reds, and when Joe Morgan followed with a walk, Bryant was lifted, already behind 3-0. Rose’s hit was his third of the game and he had one to go, No. 2.001.

“He wasn’t an easy guy to get out, for me, anyway,” said Bryant, who had his best season in 1973 at 24-12.

Rose collected his 2,000th hit after spending just 10 years, 2½ months in the majors. Cobb was into his 1Ith full season when he collected his 2,000th.

“The real milestone is 3,000 hits,” Rose said at the time. He was only 32. “But I don’t like to think about 3,000 because then I will know my career is coming to an end.”

He had a long way to go past 3,000 for that end, which only now is in sight.

NO. 3,000

Steve Rogers was taken aback slightly when contacted in Buffalo War Memorial Stadium concerning Pete Rose’s 3,000th hit. He assumed it was another writer checking on his comeback status with the Chicago White Sox, who signed him to a minor league contract after he was released by the Montreal Expos this year.

Rogers, 35, made a quick recovery.and dialed himself back in a time machine to the night of May 5, 1978 — the night Peter Edward Rose struck his 3,000th hit.

“I pitched a complete game and won it,” said Rogers. “And Pete got No. 2,999 off me, too.”

Rose didn’t get the 3,000th off a stiff. Rogers, an extremely hard thrower, won 156 games and owned a career 3.14 ERA in his 11 seasons with the Expos. In 1982, he was 19-8 with a league-leading 2.40 earned run average, finishing second to Philadelphia’s Steve Cariton for the Cy Young Award.

That night, Rogers was on his way to a 13-10 record and a 2.47 ERA, second best earned run average in the National League that season. In the third inning, with 37,283 in Riverfront. Rose pounded one off the plate that bounced high to Rogers.

“I knew I had to hurry, so I tried to catch it and throw it at the same time and dropped the ball,” Rogers said.

Official scorer Earl Lawson ruled it hit No. 2.999.

“I was running” hard,” Rose said. ‘Boy, I never ran so fast in all my life.”

When Rose came to bat in the fifth, Montreal led 3-1. He did something that angered Rogers at the time. He asked plate umpire Jerry Dale to give Rogers a new baseball.

“I told Jerry, ‘Get me a good ball because I’m gonna get me a knock (hit),’” Rose said.

Rogers glared.

“I wanted a nice, white one,” Rose said. “The Hall of Fame asked me for the one I hit for 3,000 and I wanted them to be able to read Chub Feeney’s name on it.”

No. 3,000 was no bouncer off the plate.

Rogers had no chance. The count was 1-and-0, two outs, nobody on.

“I threw what I call my cross seam fastball, a mediocre one,” Rogers recalled.

Rose blasted a single to Cooperstown, a scorching one-hopper in front of left fielder Warren Cromartie.

“That wasn’t the first two-hit night by him off me,” said Rogers. “And I don’t think it was the last. He had 2,998 other hits before those, you know. I figured, ‘What the heck, I’m gonna go right at him. I’m not gonna walk him. The big anger, with all the publicity, was to be too careful. The game was on the line. If I walk him, I could get in trouble with all their big guns coming up.”

After the 3,000th hit, Cromartie threw the baseball to shortstop Chris Speier and with a nice touch of irony, Speier threw it to Montreal first baseman Tony Perez, Rose’s teammate with the Big Red Machine. Perez was dealt to Montreal after the 1976 World Series season.

“I wanted to throw the ball into the grandstand and make that cheap son of a gun buy it back,” said Perez, now reunited with Rose and the Reds. “But really, I wanted to be the guy to give him the ball. I’m glad I was there. It felt as if I was doing it myself. It was a good feeling because I played so long with the guy and he’s a person I care for.”

Rogers, new ball in hand, stood patiently on the mound as Rose listened to the standing throng chant, “Pete, Pete, Pete.” Rose was near tears, but Perez took the edge off by nudging his buddy and Rose doffed his cap.

Rose, playing third base, was in the last year of his contract that season and was about to embark on his 14-game hitting streak. At the end of the season, the Reds and General Manager Dick Wagner decided Rose wasn’t worth $450,000 for the next season and Pete departed for Philadelphia.

Now, Rose is baseball’s all-time hits leader, not only playing, but managing his old team, the Cincinnati Reds.

Ironically, on the day Rose reached 3,000, he said Ty Cobb’s 4,191 was out of reach.

“I only wish I could play 23 years, like he did. But I realized I had a chance at 3,000 when I reached 2,000 and they told me Cobb had 1,890 at the same time of his career.”

He made it in his 23rd year.

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

NO. 4,000

It seems strange to say it — considering only one other player in major league history had ever done it — but when Pete Rose got career hit No. 4,000, it was sort of a letdown.

“I guess it’s because I’m so anxious to do the other thing.” Rose said April 13, 1984, after doubling off Philadelphia’s Jerry Koos-man in Montreal to reach 4,000.

“The other thing,” of course, was Ty Cobb’s major league record of 4,191 career hits.

“This (4,000 hits) is just something you have to do along the way. It’s a helluva plateau,” Rose said, “but when you approach the season and know you’re going to get 10 hits (which was all he needed entering the ‘84 season), you don’t get as revved up. It wasn’t really anticlimactic, but I knew I was going to do it.”

A lot of people thought Rose would do it in Cincinnati two days earlier.

Now that would’ve been something. He’d have done it in his hometown in front of people he’d played for for 16 years. The Cincinnati Reds had printed thousands of “I was there” certificates. All Rose needed was one hit.

But he walked four times before leaving the game for defensive reasons in the eighth inning. And so the path to 4,000 extended out of the country and wound through two more days.

Only a handful of writers not connected with either the Phillies or the Expos bothered to go the extra miles with Rose. And most of those who did, hoped Rose would get the 4,000th hit quickly so they could go back home. It was as if even they sensed that 4,000 wasn’t the real story. That

The real story — the home stretch in the race to beat Cobb — was a year or so away.

And on a cool day in Montreal, his first game as an Expo in front of the Montreal fans, Rose made 4,000 a formality in his third at-bat.

Batting, right-handed against the left-hander Koosman, Rose sliced a double down the right field line to set up a two-run inning for Montreal, which went on to beat Philadelphia, Rose’s former team, 5-1.

“I wanted the pitch down and away, and I got it up and away,” Koosman said. “If he’d taken it, it would have been a ball. It’s the kind of pitch that normally a hitter makes an out on. And he turned it into a double. You feel a little bit depressed about giving up the hit, but you’re also a little glad for him. It was some kind of super milestone.

“Him getting the hit off me didn’t bother me,” Koosman said. “Him scoring DID bother me.”

Something else bothered Phillies third baseman Mike Schmidt.

“I was standing out there freezing while the fans were clapping,” he said.

After the game, Rose conducted a pretty subdued press conference, seemingly anxious to get it over with. For once.

“Baseball is nothing but peaks and valleys,” he said. “This is one of the higher peaks that I’ve ever achieved.”

But he, better than anybody else there, knew it would not be the last.

Mt. Cobb was in the distance.

About the Author