Michele Russo, author of “Beautiful Feet: The Story of Maud Elizabeth Hoyle”, takes this to mean that, although her great aunt’s age was against her, her performance as founding pastor of the Evangelical United Brethren Church on Columbus Avenue in Springfield and the persistence she showed in going to nursing school to prepare for mission work helped her to meet the “high standard of ability and character” expected of those sent into the field.

RELATED: Part 1: Stained glass in Springfield church inspired woman to tell story of its courageous founder

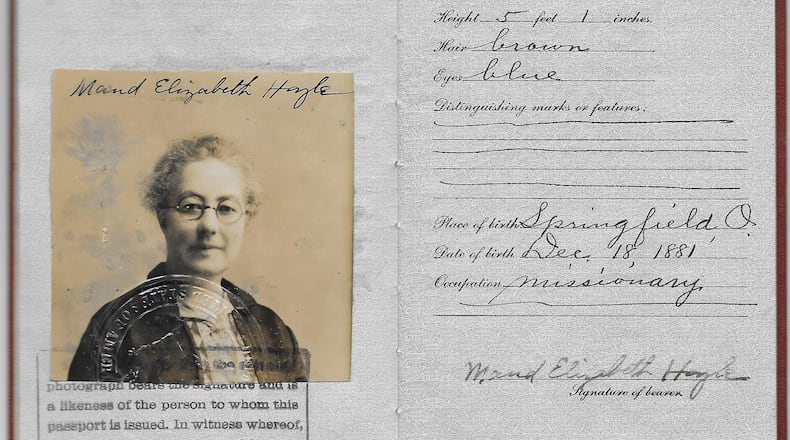

A petite 5-foot-1, Rev. Hoyle had reason to seek assurance in God’s guidance and protection as she sailed from New York to the West Africa of the 1920s. The array of predatory animals and insects was well known to her; a probable stop at the first center for the study of tropical diseases while in Liverpool, England gave her a sobering look at other health risks; and the very names of the buildings at the United Brethren’s Rotifunk mission west of Freetown on the Bompeh River, bore witness to the slaughter 22 years earlier of more than 1,000 people, many of them missionaries, when locals rose up against the British and all whites during what was called the Hut Tax War.

More Tom Stafford:

Not only was the dispensary at which Hoyle would work named for murdered doctors Marietta Hatfield and Mary Archer, but the worship center was named the Martrys Chapel, and a separate memorial to the five martyrs was a reminder why the United Brethren required all their missionaries to work with black pastors, whose partnership was critical to addressing the elephant both in the room and on the continent during the era of imperialism.

Just as her service was carried out in the context of conflict in the human family, Rev. Hoyle, though excited to begin the work she had dreamed of doing, was conflicted about leaving her own family. Grieving for her father’s recent death, she harbored deep concerns about her recently widowed mother, Ida Virginia Hoyle, concluding her appeal that others pray for and look after her mother by stating a simple truth: “She will be quite lonely after my departure.”

Her mother, too, felt conflicted, both wanting to keep her promise to God that she would give Maud’s life to Him, but longing for her daughter’s companionship.

While adapting to the unrelenting humidity and constant swarms of insects, Rev. Hoyle received a swift and uncomfortable baptism in the miseries of families of Sierra Leone who sat on benches outside the dispensary listening to Gospel before entering for treatment. In a stunning note written during her second tour of duty at Rotifunk and regional dispensaries at Moyama and Taiama, Rev. Hoyle describes the overwhelming suffering:

“Here comes a man with a downcast look. He is full of leprosy, a mass of corruption, dying bit by bit. Following him is a child of about 1 year of age. The little hand is ready to drop off from the wrist. From a sore in the thigh you can see up into the abdomen. The mouth is sore it can hardly swallow, yet it tries to nurse from the mother’s breast, which is so swollen from elephantiasis it hangs into her lap….”

In subsequent sentences that ultimately appeal to the faithful back home to support the struggle, Hoyle also captures a missionary’s sense of being overwhelmed by the mere scale of a tsunami of suffering and the obstacle it presents to her ultimate goal of introducing them to God.

“As we meet these cases day after day among all types of people — some eager and willing to hear the Word, others obstinate and impatient — we have cause at times for rejoicing; then at other times we do not dare to think, only trust, knowing if we continue to do His will the people will someday know Him, believe in Him and surrender their lives to Him. For this we pray and labor day by day. Will you join with us in this great task?”

There were, of course, compensating joys:

- The friendship of fellow missionary Nora Vesper, whose service from 1915-1955 would make her an institution at Rotifunk and who had taken on the responsibilities of caring for a child whose mother died during childbirth.

- Her work with the boys and girls she taught at separate schools designed to prepare them for work and home life.

- Her friendship with black pastor at Rotifunk, James Alfred Karefa-Smart, and the daughter he named for her.

Her relationship with Smart was cemented in times when they worked together with chloroform saving lives. Once, he assisted her as she cleaned, sewed and bound the feet of a patient who had been run over by a train before sending him to Freetown. In another instance, he helped by “drawing the piece of the lip together” of a boy whose mouth had become a running sore and then to decompose in the weeks after a cut had gone untreated.

Written at the end of her first term of service, Rev. Hoyle’s report of 1923 shows a woman who has managed under difficult conditions to remain the bright, motivated and faithful person who passed the Boxwell-Patterson Exam, made her way through seminary, built a church and then went to nursing school to make her mission work possible.

“I believe it would be easier to tell what I have not than to tell what I have done. But, as a summary, I will say that I have filled the office this year of a surgeon, physician, nurse, optometrist, teacher, preacher, itinerant (traveling preacher), anesthetist, dentist, dress-maker and tailor ….. I only wish it were possible to remain longer.”

Rev. Hoyle’s third tour of duty, a three-year term of service begun in 1927 was served in Kono, an eastern region of Sierra Leone and included an encounter in the isolated countryside with a group of head-hunters and cannibals who made her traveling companions nervous.

“Here I found people different (and) the language different,” she wrote. “While I had the same work, it was carried on in a different way,” adding reflectively, “sometimes I thought I was different, too.”

“In Djiama, beside the hospital work, I carried two sewing classes a week for the (girls) school, took my turn leading the women’s classes, itinerating, preaching and prayer services. The greater part of the year I made up 17 feedings a day for motherless babies.”

In her final year of service, Rev. Hoyle returned first to Rotifunk, where records indicate she found success enough to cheer here and failures enough to keep her humble then was off for final service in Taiama. There she again served as a jack of all trades, treating 4,249 patients, extracting 24 teeth, performing two minor operations officiating over 59 religious services with 1,615 in attendance and serving as the postal agent for the village (the position of chief cook and bottle-washer, apparently having been filled).

LOCAL HISTORY: Springfield Then and Now: Main Street

She by then had become the truly seasoned missionary the Rev. T.B. Williams, pastor of the mission at Taiama, wrote about in the October 1930 issue of The Evangel, the newsletter of the Women’s Missionary Association of the United Brethren in Christ.

“When she took over, the crowds of folks came pouring in from every direction. The fame of this wonderful woman, as she is generally and rightly thought to be, spread rapidly as fire among the stubble into the remotest corners of the chiefdom and far beyond its frontiers into neighboring chiefdoms.”

Noting at the end of his story that “Miss Hoyle is on the bosom of the Atlantic sailing homeward,” Rev. Williams conclude that “young and old, near and distant deeply regret her departure and unanimously express the sanguine hope for her return at the expiration of her furlough.”

She would not. Forty-nine years old, with cataracts clouding her vision, the woman who had lost two grandparents while in service and whose mother was blind and in failing health, decided, at last, to return for good to her Springfield home.

By then, Maud Hoyle’s mission work had been accomplished, in both senses of the word.

Note: This is the second of three stories on 1920s Springfield missionary Maud Elizabeth Hoyle

Next week: Maud Hoyle and the resurrection of history, a commentary.

About the Author