Stafford: Cosby received grandma’s tough medicine

Part II: A blossoming nightmare

Although life at her mother and stepfather’s home would never be pleasant for Lula Cosby, school had offered her both a refuge and a place to shine.

“I began high school with dreams of academic grandeur, proud to have graduated from grammar school with straight A’s, but prouder yet to be the first in any known generation of Mother’s family to achieve a grammar school education.”

The account she wrote later for a class at Clark State Community College is of a young, promising girl beginning to blossom.

“The first year at Harrison High School in Junior Orchestra, I moved from the pack to first chair viola player and at summer breaks was informed by Mr. Borg, the school’ s orchestra leader, that I had earned a seat in school’s 200-member symphony orchestra come September.”

Stafford: Clark County faces dental health issues

She had other talents as well. “The Clown,” one of her watercolors, was selected for the Chicago Board of Education student art exhibit at the Art Institutes of Chicago. “With good grades, I felt a college degree via scholarship was imminent.”

“Then,” she writes, “the nightmare began.”

The prelude to the nightmare began taking shape on a Saturday when Lula arrived home after a bike ride to the store to discover her panties were stained. She spent the weekend anxiously trying to wash the stain away.

Two days later, when she heard her mother call, “I immediately started crying,” Cosby said, because she knew she was going to be punished. She wasn’t. Her mother instead went to another room, brought back a feminine napkin, tossed it to her and, with no further explanation said, “Here, put it on.”

That day at school when she jumped through the ropes for a turn at double-dutch during recess, the pad fell out and her world began to spin. As the kids laughed, she grabbed it off the ground and ran. Not knowing who to ask, feeling the shame of ridicule, and unable to figure out how to penetrate a thick wall of taboo, she started a routine of sitting silently in the bathroom stalls and listening to the other girls talk.

“That’s how I found out about what was happening to me.”

Stafford: Springfield men bring new life to old engine

But that shadowy knowledge was not enough to protect her the summer she had trained so hard with the Chicago Youth Organization’s Track Team and was allowed for the first time to spend the night away from home with her stepfather’s cousin.

“We did not know at the time that his cousin … was a ‘working girl,’” Cosby said. “On the weekends, she would go out and prostitute and she would leave her two children home alone. During that weekend, an older boy who lived up on the third floor took advantage of me. I had no concept of what was going on.”

“I’m telling him no, and he’s saying, I remember his words, he said, ‘It’s OK as long as you stand up.’”

As school started, “One of my girlfriends said ‘You sure are gaining weight.’ And I’m looking at how round I am, and I started wearing over blouses.”

“One Sunday morning, I was singing in the kitchen and washing dishes when my Mother looked over and said ‘Are you pregnant?’”

“I start balling and crying.”

Stafford: Cold weather leads to conflict

In the aftermath, she said, “The boy denied it, the boy’s mother denied it, and my mother wanted to send me back to Mississippi to live with my Grandmother because I had disgraced them.”

She remembers this as "the only time I can remember my stepfather coming to my aid. He said: 'Have you asked her what she wants to do?'"

She didn’t want to go back to Mississippi. She didn’t want to give up her baby. She didn’t know how she’d raise him. But the girl whose grandmother had told her she could do anything she wanted to do decided she’d find a way.

It started with crochet. She’d always liked doing it, so she started making doilies. “I’d starch and stack them in a paper shopping bag, and I sold those door to door.”

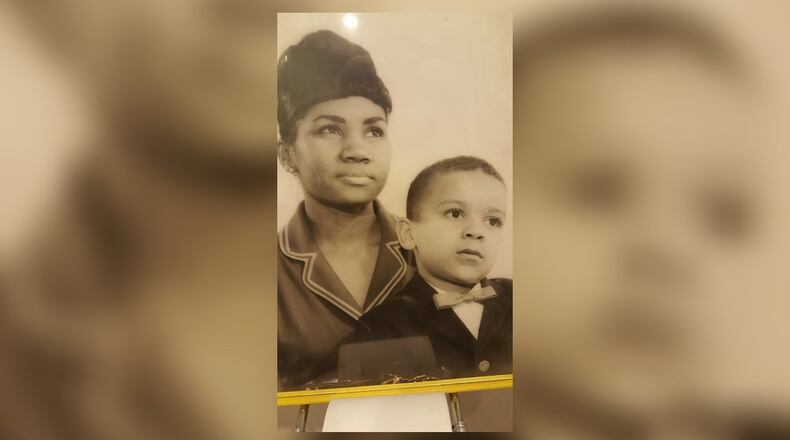

She took that money to a wholesale house to buy pantyhose she could then be sold at sub-retail prices, giving her a higher profit. When her son, Raphael, was born March 21, 1955, she crocheted all his clothes as well.

At a time when “bad girls” weren’t allowed to attend regular high school with “good girls,” after delivering, she used a girlfriends’ home address to get back to school.

“I didn’t want to apply to a trade school, they called them continuation schools at that time,” she said.

Arriving at Crane High School, she ran into a program meant to get bright students, identified by IQ tests, back on track. But at 16, she was also working from 4 to midnight at R.R. Donnelly and Sons printing, where her mother worked. Eventually, the time spent in school, at work, and then looking after her son exhausted her.

Stafford: Advice on how to survive a pre-schooling

“My grades were horrible, so I stopped going to school,” she said.

Then the girl who had one angel in her grandmother had another less likely angel stepping forward – a homeroom teacher whose hands often shook because of his struggles with alcohol. Weeks after she had disappeared from school, he contacted her and asked her to come back.

Later, when she asked him why, he said, “I could not allow you to waste your talent.” Mr. Conroy, the school’s principal, agreed, and the three of them came up with an agreement to get her to graduation.

“I could not let anyone know that I had a child or (the principal) would be forced to remove me from the school and transfer me over to the continuation school,” she said. She also had to promise that she’d have near perfect attendance as a form of restitution for her missed time.

In exchange, they would bend the rules to allow her to continue. As it turned out, for logistical reasons, this arrangement soon required a distant cousin to accept $100 for a yellow-and-green four-door, slightly rusted 1951 Chevy and the intervention of another angel in the form of an uncle who volunteered to teach her to drive.

The rest was up to Cosby.

When graduation arrived, “I paid for the parent-student luncheon and I sat there by myself, because nobody else came. I paid for my graduation, my pictures, everything. I was voted ‘Most Courteous” by the graduating class of 1959. She even invited her best friend, Bruce, to take her to the prom. That period was lonely, she said, but it made me so determined. Because if I had not recognized before, I knew then that to survive, I had to depend on myself.”

Further proof of that came the Saturday her stepfather locked Cosby and her son out of the house because they had missed his midnight curfew. Two days later, the Tallaricos, an Italian family that rented the front apartment of a converted duplex to one of Cosby’s friends, agreed to rent the back room to her.

When Cosby moved out, her mother gave her a cast iron skillet, two plates, two glasses, two forks and two spoons – and a promise to babysit Raphael. Cosby then withdrew money she had saved in the R.R. Donnelly & Sons credit union to buy a television, a record player, a bed and a table with four chairs from a furniture store.

“They delivered those things to me the next day, and I never looked back.”

Lula Cosby was 19.

About the Author