The Ohio Department of Health doesn’t track individual cases of CRE but said hospitals and other health care providers would be required to report an outbreak of two or more cases. “To date, we have not had any outbreaks reported to us,” the health department said in a statement.

New York, Los Angeles and Chicago have been hot spots for the infections, but 42 states, including Ohio, have had at least one patient test positive for one type of CRE, according to the CDC.

The government agency’s March Vitalsigns report adds infection rates have increased from 1 percent to 4 percent during the past decade.

Dr. Thomas Herchline, medical director of Public Health – Dayton & Montgomery County, said the infections are found primarily in patients with prolonged stays in hospitals, long-term care facilities and nursing homes.

“A lot of the people that get this type of infection are very ill before they get the infection, so it’s not healthy people walking around in the community that are really at risk,” he said. “The real concern is about the increasing resistance in the infections (to antibiotics), and there just are not a lot of new antibiotics coming out. That’s a challenge internationally, not just locally or in the U.S.”

With its higher risk elderly and poorer patient population, the Jewish Hospital-Mercy Health in Cincinnati’s Kenwood area, where Burke works, is on Ohio’s front line against the often fatal super bugs.

CREs develop in patients ill enough to be treated for long periods with antibiotics. Those medicines often kill not only the body’s harmful bacteria, but also the helpful strains. In doing so, it clears the field for resistant harmful bacteria to flourish.

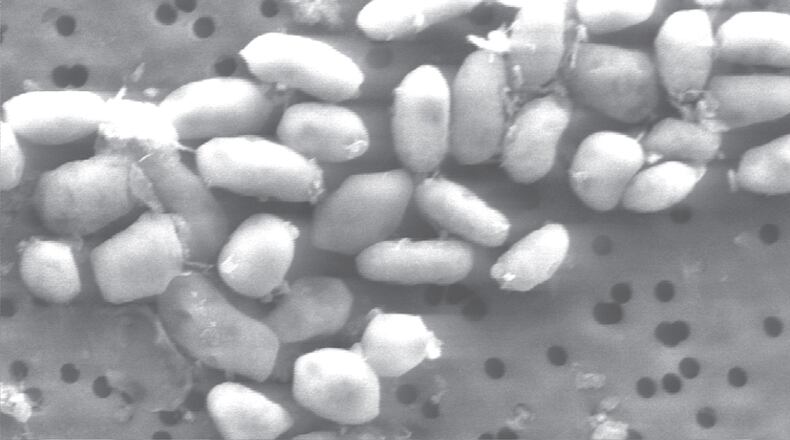

Of the CREs, Klebsiella pneumoniae and E. Coli are “the two big guys,” said Burke. Among the threats they’re associated with are pneumonia and urinary tract infections.

Like other infections, including the well known MRSA, a form of antibiotic-resistant staph infection, CREs can be transmitted from from person to person, Burke said, especially on the hands of health-care workers.

Because of that, he said, Jewish Hospital now presents awards for units with the best hand hygiene compliance of the year, part of a program that stresses “hand hygiene is as much a part of medical care as listening to someone’s health sounds.”

Kim Jerger, an infection specialist at Springfield Regional Medical Center and Mercy Memorial Hospital in Urbana, said that, like hand hygiene, detecting and responding to CREs is part of the normal process that also watches for other bacteria and infectious agents.

“We’re pretty vigilant,” he said.

The discovery of harmful bacteria in urine cultures or others tested in the hospital’s microbiology lab sets off a response — Jerger is informed; patients are isolated in their rooms; doctors and nurses are required to wear masks, gowns and gloves when treating them; and the housekeeping staff is informed.

In addition, the hospital pharmacy is called on to ensure that the patient is using the best antibiotic for the type of infection and its location in the body.

This close management of treatment is what Jewish Hospital calls antibiotic stewardship, something Clark County Health Commissioner Charles Patterson sees as an area in which public health departments contribute to the fight against CREs.

“The message is that if you are on antibiotics, you need to take the entire course of antibiotics, even if you’re feeling better,” he said. “You want to make sure you’ve killed off every single one of those” harmful bacteria, so they cannot survive to become resistant.

The Clark County Combined Health District may launch a public education campaign about the importance of hand washing and hygiene to infection control, Patterson said, in addition to keeping in touch with infection control specialists at Springfield Regional, the Ohio Valley Surgical Hospital in Springfield and long-term care facilities.

Jerger seconded the idea, saying “effective hand hygiene is the single most effective way to fight the spread of disease and illness.”

Like multi-drug resistant tuberculosis, CRE infections are “not something we’re having a lot of problems with,” said Patterson, who added that he would like it to stay that way.

“We’re more than happy that the CDC and others are on top of these things,” he said.

But those fighting the infections can’t guarantee Ohio communities will forever be protected from CREs.

“These organisms are smart, and they’ve found ways to protect themselves,” Jerger said.

Burke added that because patients move from place to place, keeping CREs out of the wider community requires collaboration among hospitals, nursing homes and public health systems, a collaboration that bacteria have, in the past, found ways to outwit.

“At one time MRSA was only acquired in hospitals, too,” Burke said. “That’s sort of the concern now.”

About the Author