Grant talked about Jayda, who died on May 30, 2022, publicly for the first time in an interview for the Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation Medical & Health Symposium. Grant’s interview was titled, “Balancing the Effects of Mental Health, a Personal and Professional Story.” It was posted online Thursday.

The two-part interview with Tony Coder, the executive director of the Ohio Suicide Prevention Foundation, touched on Grant’s career journey and his own challenges as a player and a coach. He also spoke about the issues he and his program dealt with during the pandemic.

The main focus of the 75-minute session was Jayda. Both videos are free to watch through May 17 at https://mhs.digitellinc.com/mhs. Registration is required.

The Dayton Daily News reached out to the Ohio Suicide Prevention Foundation to get Coder’s thoughts on Grant sharing his story. The foundation sent this response on his behalf: “I am so humbled and grateful to Anthony and Mrs. Grant for sharing their journey with the public so that others might be helped. Coach Grant’s strength in talking through his family’s unimaginable tragedy shows the type of man that he is and family that the Grant’s are — incredibly caring and able to share his life and faith in order to help other individuals and families who are impacted by mental health.

“If someone is struggling with mental health or thinking about suicide, please call or text 988 to be connected to a trained crisis professional.”

Below is an excerpt of Grant’s conversation with Coder.

Coder: Before we talk about Jayda, how hard is it to talk about mental health?

Grant: Well, this is a new experience for me, Tony. I’m just being honest with you. Obviously, you know a little bit about our story with our daughter, but I think for me nothing happens in the moment. It was kind of a build-up for me and my family over years. My awareness of mental health and some of the challenges and the importance of learning more about it was heightened because of our personal experience but also because I saw what was going on in other places across the country and quite frankly in athletics. Some of the things that I was aware of post-COVID, some of the struggles that college athletes or students or athletes at the professional level were having, it was close to home for me. But it wasn’t something that I knew a lot about, and I didn’t know the resources that were available to be able to learn more. I think this process for me is kind of the next step, so to speak, as I navigate my new reality of life as we go forward after our tragedy.

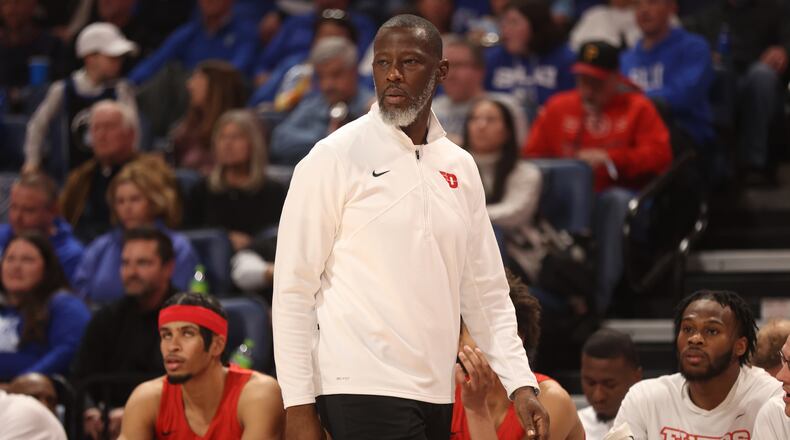

University of Dayton Men's Basketball Head Coach Anthony Grant will speak in an on-demand session at #MHS23. Watch his session "Balancing the Effects of Mental Health, a Personal and Professional Story" beginning May 4.

— Ohio BWC (@OhioBWC) May 1, 2023

Registration is free: https://t.co/iDdi15Qix4 pic.twitter.com/8r0oJVA5k2

Coder: We’re going to talk a lot about Jayda today. Tell me what kind of little girl she was. What kind of daughter was she?

Grant: She was our baby girl. My wife and I have three boys. We had our oldest son, AJ, and then we had a second son that we lost at eight months pregnant, Brandon. He was stillborn. The impact of that for my wife and I was something that was hard to deal with. Going through that was probably one of the most difficult experiences for me personally and for my family. But we are people of faith. The Bible tells us the plans the Lord has for us are good and that our faith in Him will sustain us, and that’s been true for us. Sometimes when bad things happen, you ask why. His word tells us that all things work for the good. Part of that experience showed us how that could happen. We had some dear friends that years later went through something very similar to what we went through, and we were able to be us a source of strength for them because of what we experienced. So I saw that as His word being true, that there was good that came out of something so tragic.

We were able to share our story years later. It was actually myself, coach (Billy) Donovan, and John Pelphrey. We were all on the same staff, and we all had a similar experience. We were able to share that publicly. The feedback we got sharing something so private and so difficult and hearing the impact that it had on other people that are going through something similar really gave me a different perspective, and it was a needed perspective because of that pain. We were able to have another son (Preston), our second oldest, about a year later, and then 15 months later came Jayda and then our last son, Makai. So my appreciation for what women and my wife actually go through to bring life into this world took another another step in terms of the respect and and understanding the sacrifices they make because it was a difficult journey for us.

Jayda was a joy. She was quiet. She loved being around her family. She loved friends. She loved sports. She was a natural athlete. She was good in school, a vivacious reader. She was artistic. Played sports really from elementary school: flag football; basketball; softball. Then as she got older, her passion became track. She was a great athlete. She loved to run. She had good speed.

Coder: When did you first start noticing Jayda’s struggles with mental health challenges?

Grant: During the pandemic, probably in the fall of 2020, she shared some things with us that we really weren’t aware of that she was going through and struggling with — more along the lines of anxiety and some other things that had happened. At 19, like most young people, she was at an age where she wanted more independence in terms of being able to make her own decisions. That 2019-20 year was her freshman year in college at the University of Dayton. She was on the track team in high school and was doing really well. In her senior year, playing powderpuff football, she tore her ACL. She didn’t get a chance to compete in track her senior year, but she was a part of the team with her friend group and stayed involved.

When she came to University of Dayton, she was going to walk onto the track team. She had a year of rehab she had to go through. The following year, the plan was for her to join the track team and participate in events, and then obviously COVID hit. That fall is where we started to get some indication that things weren’t necessarily right. After a year of college, you think it’s natural for kids to want maybe a little bit more of their own independence and make their own decisions. She certainly showed some of those signs. As a parent, that’s difficult sometimes to figure out, ‘OK, what exactly is going on here.’ I would say that we didn’t necessarily have a complete grasp of it. We tried to put pieces together here and there in terms of what she was going through and tried to offer support or advice and some boundaries. As we moved forward, you saw it escalating into some other things in terms of decisions she made with her medical care that we found out about that concerned us.

I would say it was a combination of the pandemic and the isolation with her injury taking away something. In hindsight, that was a vehicle for her to build relationships and establish friendships with her classmates, people that had a common interest. At that time, as we all know, there was a lot going on. Not only did we have the pandemic, but there was also the social or racial pandemic that we all experienced with the death of George Floyd and everything else that was going on politically and socially not only in our country but across the world.

Jayda was someone that was very intuitive and very interested in helping people. Her heart and her vision of what she thought the world should be and how we should engage with each other was pure. All those things together impacted her. She shared with us somewhere in that time that she considered herself to be non-binary. At the time, I really didn’t know what that meant. Her friends referred to her as Jay. It was the first time for me hearing the pronouns and understanding how she felt and trying as a parent to grasp that and to be able to understand that and let her know that she was loved, and it didn’t matter to us how she chose to identify, that we loved her for who she was. All of that all together, it was kind of like a perfect storm.

She wanted to be able to navigate that at 19, feeling like she needed to be an adult on her own. That’s difficult as a parent because at a certain age, through HIPAA, the medical profession says that your child is no longer a child, that they have the ability to make decisions for themselves. As a parent, that’s really difficult to know that your child is struggling. You live with that child every day, but in the eyes of the law, of the doctors, they’re at an age where they can make their own decisions, and those decisions, along with some of the mental health issues of anxiety or depression or identity or being able to fit into a group and how that changed during COVID, I say it was kind of a perfect storm that all hit at the same time. As parents, we really didn’t see that coming. Certainly, you look back, just trying to to navigate it, and there’s guilt and there’s obviously a lot of heartache and a lot of pain.

Coder: How hard was it to find help?

Grant: That’s probably the thing that’s the toughest. As a parent, the thing you live for is to be there and to provide for your children everything they need. I think that was probably one of the most difficult things, trying to navigate that boundary of having a 19-20 year old that wanted independence with what you feel as a caregiver and as a parent. When she did allow us or my wife to interact, it was difficult to be able to get the caregivers — whether it was doctors or mental health advisors — to understand what we were saying. She had a an attempt (on her life) a few months before she took her life. We felt there just wasn’t enough shared information, or there wasn’t enough of an understanding of what we were seeing and what we were going through to try to get her the help. She was actively seeking help and was in the process of getting help. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to get the help that she needed and we needed in time to have a different outcome.

Coder: Trying to find help, trying to find care and Jayda dies by suicide, was there anger or frustration with the system?

Grant: I would say, personally, for me, there wasn’t anger. I would say from my wife there was because she made some phone calls to the place Jayda was going for care. Some things had changed unexpectedly. Her medication was changed from what she had been assigned when she was in the hospital. My wife was really proactive and trying to say, ‘Hey, why was the medication changed? Something needs to happen based on what we’re seeing.’ There wasn’t a return phone call. There wasn’t any anything that was done, in her eyes, to help, and maybe had something been done, it could have been prevented. At the end of the day for me, it wasn’t going to change our outcome. I saw no sense for me personally of having that anger or blame. The loss was immense. For me, it was more about that and the fact that we had three other boys and a family that I had to be there for. As difficult as that was, I tried to try to put things in their proper perspective in terms of how to deal with that, but certainly you go through a loss like that, and it cuts through your soul. There’s times where you ask why. What could I have done differently? What what could have been different in the system?

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for those ages 10 to 34. Just seeing how stressed the system is with some of the mental health crisis that our country is going through, that probably the world is going through, I understand better some of those challenges. I can empathize with how difficult it is for mental health providers to be able to give the care that’s needed with the urgency that is needed for each individual family.

My hope is that our story may encourage someone that may be struggling, as our daughter was, or maybe a mental health provider that feels like they’re not making a difference. No, you are making a difference, and this is much needed. Maybe a family that has experienced what we’ve experienced will look at it and say it’s possible to get out of bed the next day and to continue to move forward. For us, it was faith. It was friends. It was people like (Coder) that reached out and allowed us to put a foot forward the next day and the day after that to continue to try to gain strength. That’s why I’m here. This is my first time publicly speaking about what we went through. For me, this is cathartic in terms of helping me, helping our family. At the end of the day, my hope is that we can help others and give purpose to the pain that we experienced. I want to try to help as much as we can.

Coder: What recommendations do you have for someone who’s trying to seek mental health care or struggling with mental health issues?

Grant: I would say being able to speak about what you’re going through. That was difficult for my daughter with everything that she was going through with her age, being able to feel heard enough to really come to us to talk about it. ... Tony, a lot of it is what you guys do. You guys do phenomenal work. And until after what happened with my daughter personally, I didn’t know it existed, and I wish I would have prior to because I think the work you guys do saves lives. I can sit here because of the profile that I have as a coach, and if it helps somebody else know where to go to find resources, whether it’s therapists or books or just how to talk to their child or their significant other or family member or friend, that’s what I want to do. There are a lot of people out there that do great work in this field. I have a voice through athletics that may be able to point people to you and those resources that are already available because you’re doing great work, so that’s the goal.

Coder: Is there a new normal for you after the loss of Jayda?

Grant: I think I’m figuring it out. Really, I think this step for me being able to talk about it, hopefully, becomes a new normal, being able to figure out a way for my wife and I talk about it quite a bit. How can we honor our daughter and let her light continue to shine for who she was and and what she meant to so many.

About the Author