Among them are seven veterans of the Revolutionary War.

The project is the work of the 10-member Springfield Burying Ground Restoration Committee, an ad-hoc group of people long involved in Springfield’s public life and history-interested community.

Advised by two local attorneys, it includes representatives of Ferncliff Cemetery; the Heritage Center; the Turner, Springfield and W.S. Quinlan Foundations; and the Daughters and Sons of the American Revolution.

Credit: Bill Lackey

Credit: Bill Lackey

A rectangular plan

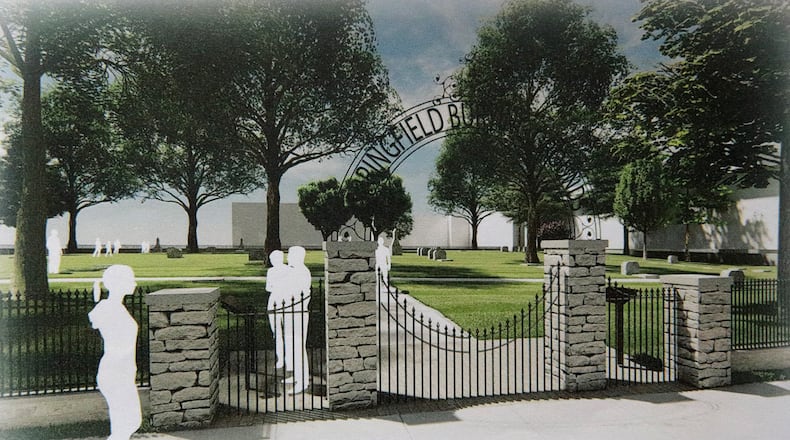

Following a plan developed by Richard Espe of MSKS consultants of Columbus, the project will front the property on Columbia Street north of Ohio Valley Surgical Center with a wrought iron fence. At the center of the fence and set off by stone pillars will stand a wrought iron gate displaying cemetery’s name when community founder James Demint donated the land for it in the first decade of the 1800s.

The gate will be set back from the sidewalk the edge of a small entrance plaza built of tan pavers.

The overall design plan follows the rectangular shape of the property. Its main feature is a 5-foot-wide rectangular walkway of light colored crushed aggregate that, from above, looks like a picture frame placed in the lot so the grass fills the interior, where the picture would be, and leaves room for a consistent grass border around the exterior.

The design also calls for two walkways that divide the interior of the walkway into what look like four panes of window glass. One divider be a five-foot concrete walk edged with the same color pavers set on a north-south axis, extending from the entrance to the top of the above described picture frame.

The other, made of aggregate, would slice the interior in two horizontally.

At the center would be a circular plaza with a flowerbed at the center, from which would rise a statue of a community pioneer, likely Demint, designed by Urbana sculptor Mike Major.

One reason for the relatively simple design is to minimize the amount put atop a graveyard where the location of the burials is largely unknown.

Preliminary site work is underway and a construction phase expected to begin early next year with a goal of a public rededication of the cemetery on Independence Day 2022.

How it came together

Although a restoration of the cemetery had been considered before, the current effort began when local genealogists Bob and Flossie Hulsizer found a business card slipped into the crack of one of the cemetery’s deteriorating monument. The card was from a descendant of a Revolutionary War veterans buried at the spot asking whether something might be done to improve the grounds.

“This was 2014,” said Bob Hulsizer, “and I got to think somebody should do something about this, but I don’t have any money to do this kind of thing. So, I got the nerve up to do down and talk to John Landes (executive director) at the Turner Foundation.”

Landes embraced the idea and referred Hulsizer to Kevin Rose, the foundation’s Historian.

Rose said the most extraordinary thing about the cemetery – what makes it a treasure for Springfield -- “is the fact that it’s still there,” which is a rarity in most communities. Rose gives credit for pioneer descendants and Lagonda Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution for helping to preserve the cemetery over the years.

To encourage the effort, Rose said, “we engaged a landscape architecture firm (and a surveyor).” Knowing the price tag would beyond its means, however, “we encouraged the formation of a group.”

“Fortunately, we got Tom Loftis involved,” Rose said. “And there is no better community advocate.”

Although he characteristically minimizes his role, Rose said that without Loftis’ organizational skills and credibility with dozen donors who have provided a lion’s share of the funding, the project would have remained an idea for the foreseeable future.

Paul “Ski” Schanher said that he, like many who are involved, “really didn’t realize what we were getting into” when signing up for the project and credits Loftis for having “led this group through a maze.”

The maze of work included tracking down deeds to establish the property was city owned, which allowed the city to donate the property for a $1 fee; checking with Ferncliff staff about choosing appropriate ornamentation for the cemetery and repair of headstones; and considering the logistics of doing work on grounds where the most of an estimated 160 burials are unmarked.

The effort also drew the involvement of community stalwarts including John Paulsen, who most recently helped United Senior Services rehabilitate the former Eagles Aerie into its current facility; Al Wansing, with his deep interest in city history and knowledge as the longtime City’s Service director; and Darryl Kitchen, current administrator of Ferncliff Cemetery.

But the project reached out to others as well.

Schanher, for instance, helped to lead a subcommittee that held focus groups with community members who “gave us a lot of insight” into what people might look for in such a project, including credit given to the city’s pioneer women.

Linking the past and future

Not lost on anyone is the project’s contribution to the effort that has gradually filled in empty or decayed properties in the downtown like a dentist doing restoration work.

Schanher, a retired dentist, a deeply religious man and the driving force behind the Springfield Civil War Symposium, said he’s honored to be part of a project “to help with the beautification of downtown Springfield” and, at the same time, “the resurrecting of Springfield history.”

That this involves a burying ground seems to add icing on the cake.

Said Schanher, “It’s going to be beautiful.”

How to donate

Organizers soon will begin raising $300,000 for an endowment for the Burying Grounds’ upkeep so that it does not fall back into disrepair. Contributions can be made to the Springfield Burying Grounds fund at the Springfield Foundation.

About the Author