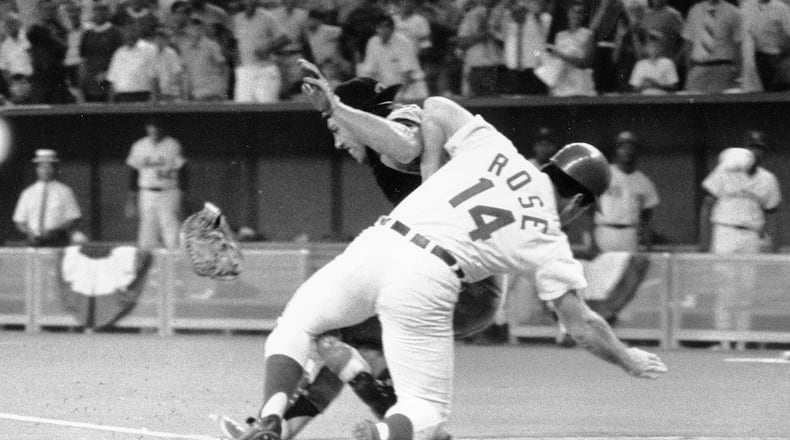

How long a sports world that’s gone all-in on betting will keep Rose, its all-time hits leader, out of the Hall of Fame for gambling infractions is unclear. Undisputable is the hit Rose delivered in that 40th All-Star game will stir up dust around home plate and among fans for as long as baseball is played.

And the content of the bench-clearing arguments of that All-Star occasion are the same ones covered in the Springfield sports pages during July of 1944 — the year Rose turned 3 and 3 years before Fosse was born.

A fatherly interest

It wasn’t and isn’t unusual for hometown sports editors to take a near fatherly interest in the athletes their pages begin reporting on.

For both personal and professional reasons, the Springfield News-Sun’s Homer Circle was very much in that mold and tradition and why he invited local stars whose careers continued after high school to write and call him whenever the spirit moved them.

As I mentioned in a column on June 2, it was a dispirited and somewhat homesick Harry “Lefty” Amato who wrote to Circle at the end of June of 1944 from York, Pa., home of a Pittsburgh Pirates farm club.

“You should have seen me the first week I was out here – they couldn’t get me out,” Amato wrote. " Now, I can’t even get on base to get out. One day I bust out three hits and the next week I go hitless. I can’t figure it out.”

In those days, when the fun seemed to have drained from the game, Amato told Circle he had one bright spot to report.

“The other night, I was on third and the next batter hit a fly to the outfield. I went in on the (out) signal and the catcher, about 200 pounds blocked the base on me.”

A frustrated Amato, who weighed 40 pounds less, but had been a dazzling star on the football field, seized the moment.

The left-handed outfielder for the White Roses team did what Pete Rose would do 26 years later.

“I hit him with a football block. He went down like a rock, dropped the apple, and we won 6-5.“ That, Amato wrote, “was fun.”

On further review

Circle’s fatherly instincts held off an immediate reprimand from the struggling 17-year-old who was far from home and at the time was feeling even farther.

‘You’re playing in a tough (league) and each ambitious rookie is ready to step in your face to advance himself a notch up the ladder,” the editor began.

Only then did he suggest Amato “keep one little thought in the back of your mind.

“The winning of any single ball game, league or pennant isn’t worth the price of inflicting a permanent injury on an opposing player …. Often, in the fight for fame, we are prone to forget some of the more basic rules of humanity.

“Just play the game hard, clean and honestly, the way you always have,” he added. “And when you get to the top the foundation you have built … will weather the storms to come.”

The anonymous letter

A day or two after sharing this story with his reader, Circle got a letter from an anonymous reader comparing him with a yet-to be-conceived Springfield Homer whose fictional son shares a first name with Bart Giamatti, who would negotiate Pete Rose’s lifetime ban from baseball.

“Having been a rabid baseball fan for a score or more years and therefore holding a particular dislike for those who attempt to ‘sissify’ the game,” the letter said, “I have just one question to ask … Have you ever seen a baseball game?

“If you have,” he ranted, “you must know that baseball most certainly is not clean, as you phrase it. Nor should baseball be clean. (My italics.)

“Baseball is not a friendly game of bean bag. It’s strictly a survival of the fittest business, and if you can’t survive then get out.” Had (Amato) “not attempted to knock the catcher out of the way, he wouldn’t have been criticized by the manager. He would have been kicked right out of the ballpark!”

The terse conclusion: “Your advice to Amato will put him out of baseball quicker than a broken neck.”

Responding in kind

Circle hit back, opening his response by saying his waste basket is the usual repository for letters from anyone “who doesn’t have either the conviction or fortitude to back up his opinion by signing his true name.”

“But rather than allow this person to force his opinion upon some growing athlete,” he told his audience, “We chose bring it out into the open.”

Agreeing that his critic is indeed a “rabid” fan, Circle focused on the “sadistic,” a paragraph in which the anonymous writer ponders how many players the leading managers of the era “have crippled in their time” while trying to establish themselves as the fittest in baseball’s Darwinian struggle.

“My, what an item to clip out for your scrapbook,” Circle writes: “‘Jones spikes player’ … may be serious … or ‘Smith breaks player’s back with smashing drive’”

“What about the families of these broken athletes who are the victims of these ‘good ball players?’” he asks.

He then describes as “callously overdone” his opponent’s characterization of the average manager’s approach to plays at the plate.

“Few body blocks are justifiable,” Circle argues, “and when they are, the player should know the safe way to hit the usually unprotected defensive man.”

To drive his point home, Circle then quotes Earl Wolgamot, manager of the minor league Springfield Giants.

Just that week, Circle wrote, the Giants, too, had a play at the plate, and a Giants player he left unnamed crashed into an opposing catcher even though the runner had been out “by a mile.”

After the player emerged from the showers, Circle said, manager Wolgamot told him what he’d done “‘wasn’t exactly dirty” but the outcome “could have been different.”

“I want you to play hard and play to win at all times,” the manager said, “but I never want to see any of my boys playing dirty with an intent to injure.”

“Those other nine guys (of the opposing team) want to make their way in baseball, the same way as you do. Respect them as opponents but keep it clean above all.”

Eighty years later

Eighty summers after Harry Amato ran over the catcher at home plate, he described to me what happened while dust still hung in the air.

“When he got up, he started at me, and they all stopped him.”

That didn’t stop the catcher – who still outweighed him by 40 pounds – from looking Amato in the eye and saying, “I’ll get you outside the gate,” which was where he was waiting when Amato emerged from the locker room.

What happened next almost knocked Amato down.

Instead of throwing a balled fist, “he came over and stuck his hand out to shake hands,” Amato said.

“He said, ‘My manager told me I was wrong when I blocked the plate.”

The manager then blocked his path, adding, “You drop it now.”

“That’s the way we ended it,” Amato said. “We didn’t end up as enemies.”

“And I don’t remember seeing him block the plate again.”

As for the collision of July 14, 1970?

Fosse ended up with a fractured and separated shoulder that nagged him for the rest of his career, likely influencing its course.

Rose was unapologetic, saying he’d intended to slide but that Fosse had left him no way to slide into home, so doing so would have been pointless.

So, Rose said he what he always did when a game was on: he played to win and ― to use the standard gambling analogy — let chips, like Fosse, fall where they may.

I was 16 that night and had my own strong opinions.

Just having turned 70, my opinion of the importance of my opinions has diminished.

What I’m more certain of is that before the dust settles on me, I’ll see new generations of fans figure out where they stand on the competing values that collide at home plate.

P.S. — The Springfield Giants’ Wolgamot, who was a catcher and manager, died three months before the 1970 All-Star game.

About the Author