During their senior seasons both Hornung and Te’o were pretty much the face of college football.

While Hornung was free-wheeling and considered something of a play-the-field beau, Te’o supposedly was a one-woman man who stoically dealt with loss when he said his girlfriend died of leukemia during the season.

But as everyone now knows, that girl didn’t exist and Te’o was either the victim of a cruel Internet hoax orchestrated by a guy who knew him or, possibly, the linebacker was in on the fabrication. No one is certain, including Hornung.

“I don’t know if it’s going to ruin the kid or not, we’ll just have to wait and see,” he said. “I don’t know if he’s going to be a first-round draft pick now — if some teams might shy away — and that’s kind of sad. It’s just so unusual and the question is why?”

As he quietly pondered the answer, the question was tossed back to him.

Hornung once was considered one of the most fabled ladies’ men in the NFL. With his good looks, charm and ever-ready embrace of life, women were drawn to him.

Take the gal who left the stands during one of his first games with the Green Bay Packers and came up to him as he sat on the bench. As the story goes, she wouldn’t leave until she got a photo with him. Always a multi-tasker on the field (he was a quarterback, halfback and placekicker), he delivered his message before security carted her off:

Meet him outside the dressing room after the game.

So with that in mind, he was asked: “Did you ever have an imaginary girlfriend?”

The question made him snort: “No…no…they weren’t imaginary!”

His wife Angela, who married him nearly 34 years ago, long after the escapades in question, just rolled her eyes and smiled:

“Maybe one. Maybe Rita Hayworth.”

Hornung grinned: “Oh yeah, I coulda gone for her.”

And with that, his laughter filled the empty Loft Theater where in a couple of hours a sellout crowd would be on hand for opening night of “Lombardi,” the play about his iconic Packers’ coach, Vince Lombardi.

Written by Eric Simonson and based on the David Maraniss book “When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi,” the play runs at the Loft through Feb. 24.

Hornung had come to Dayton to help launch the show and, at the same time, raise some money for the Visiting Sisters Program in Louisville. Run by nuns, it provides food and clothing for the poor in his hometown.

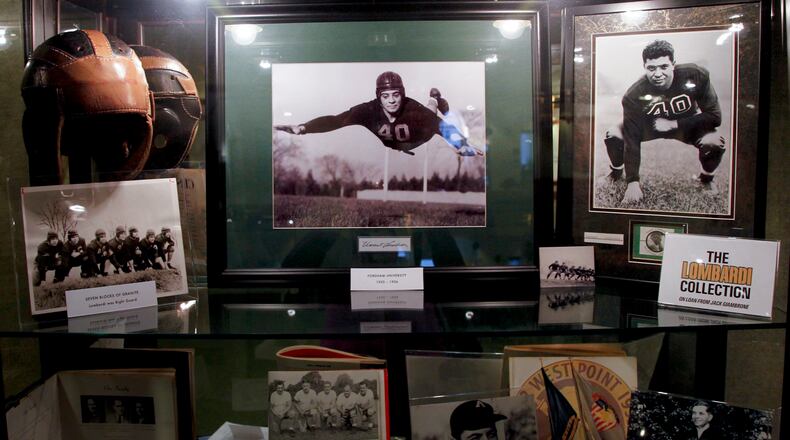

Over the years he has raised over $300,000 for the group, said Jack Giambrone, the former Sinclair Community College athletics director and current assistant commissioner of the Ohio Community College Athletic Conference, who has part of his extensive collection of Lombardi memorabilia on display at the Loft.

Friday, though, the artifacts were but a backdrop to Hornung’s colorful stories. The Golden Boy may be 77 now, but he hasn’t lost his luster. He’s still engaging, frank, mischievous … delightful.

One of the stories he recounted was about another trip to Dayton several years ago:

“I used to come in here for that golf outing, the Bogie Busters, put on by Cy Laughter. He was close with (Packers end) Ron Kramer, a Michigan guy.

“In fact I had breakfast one morning right downtown here and someone tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘Mind if I sit here?’ I looked up and it was President Gerald Ford. He was here for the golf.

“I said, ‘You’re welcome to sit here.’ But he’s a Michigan man, too, and pretty soon he and Kramer were lying to each other.”

So did one of them pick up the check?

“Are you crazy?” Hornung laughed. “They’re Michigan guys.”

A dynasty builds

After Hornung won the Heisman as a quarterback, Green Bay made him the first overall pick in the 1957 NFL draft. But the Packers were floundering back then and in 1959 Lombardi, a New York Giants assistant, was brought in as the head coach.

Immediately he announced there would be changes, including Hornung becoming the halfback, and after the first meeting quarterback Bart Starr set the tone.

“Bart came out and told the rest of us, ‘You know boys, I really think these changes could be OK and we can win with this guy,’ ” Hornung said. “Bart bought in right away.”

And he was right. Under Lombardi, the Packers would win three straight NFL titles and five in seven years, including the first two Super Bowls.

Running the fabled Green Bay sweep behind Jerry Kramer and Fuzzy Thurston, Hornung became a hall-of-fame back. He led the league in scoring from 1959-61, was MVP in ’61 and became, arguably, the best short-yardage runner in NFL history.

He credits Lombardi with much of his success, in part because of things he did behind the scenes.

When Hornung was called to active duty in the U.S. Army in 1961, Lombardi petitioned his friend, President John J. Kennedy, to arrange a weekend pass so Hornung could play in the NFL Championship Game against the New York Giants.

“Paul Hornung isn’t going to win the war on Sunday,” Kennedy said at the time. “But the football fans of this country deserve the two best teams on the field that day.”

They got one. The Packers won 39-0 and Hornung scored 19 points, an NFL title game record.

In 1963, when Commissioner Pete Rozelle suspended Hornung and the Detroit Lions’ Alex Karras for gambling, Lombardi first counseled his halfback and then quietly pressed Rozelle for his reinstatement.

“Rozelle should have suspended me,” Hornung — who was similarly upfront back in ‘63 — said Friday. “He could have suspended a lot of others, too. A lot of guys bet like I did. I’d bet $100 and never more than $500. The commissioner was making a point and the older I got, the more I understood.

“Lombardi told me to keep my nose clean. He said, ‘I know you love the race track.’ How could I not? I grew up in Louisville. But he said, ‘I don’t want to see your rear end at the track or see any write-ups about you in Vegas or having anything to do with gambling.’ ”

He listened, and a year later — thanks in a big way to his forthrightness — he was back in the game and his image wasn’t tarnished.

A neck injury curtailed his play in 1966 and a year later, when he was taken in the expansion draft by the New Orleans Saints, he was first examined at the Scripps Clinic in California and found to have a severing of three vertebrae and damaged nerve roots in his spinal cord.

“Another hit and I could have been a paraplegic,” he said. “’I walked away from the game then.”

He was 31.

While he became successful in real estate and as a broadcaster, Hornung has seen football exact a toll on his body. He’s had both hips replaced and one knee. Yet he said he’s not nearly as bad off as many of his contemporaries.

Because a different mindset ruled then, he said guys played with injuries and concussions: “We’ve got one guy, Fuzzy Thurston, who doesn’t know where he is right now. He’s in a home by himself — his wife just passed away — and he’s lost everything. He’s all screwed up. A lot of guys are like that.”

Always generous

Friday night Hornung sat in the lobby signing photographs and copies of his “Lombardi and Me” book for a crowd of theater goers and fans. The proceeds all went to the Visiting Sisters Program.

Lombardi liked that side of Hornung, especially the way he helped young players. When he’d get a paid appearance, he’d bring along young players and share his payday with them.

In the coming weeks Hornung will be campaigning what he hopes is his first-ever Kentucky Derby horse, Titletown Five, which is trained by the legendary D. Wayne Lukas. The horse won its maiden race at Churchill Downs on Oct. 28 by nine lengths but was later sidelined by a bone chip. He’s back working again and Hornung thinks they can position him for a roses run.

And next week a Hollywood group is supposed to visit him in Louisville to discuss the possibility of a film about his life. Asked who could play him, he said Matthew McConaughey had been approached.

When “Lombardi” first opened on Broadway, Bill Dawes, the actor who played Hornung in the show, came to Louisville to spend time with him.

Hornung said among other things Dawes wanted to know about some of the ladies’ man stories, like the one when the halfback supposedly went on a dinner date with a woman his football pal Rick Casares set him up with the night before the Western Division title game with the Baltimore Colts. Supposedly, he didn’t return to the team hotel until 7 a.m.

Friday, Hornung — who said he hadn’t expected to play back then because he had been hurt — claimed the woman had gone home after dinner and he then had had drinks with his pal, Baltimore lineman Jim Parker. He said he returned to his room at 4, though he couldn’t sleep.

Regardless, early that morning he was approached by Lombardi, who, unaware of the nighttime cavorting, had asked him how he felt. When Hornung said fine, Lombardi told him he was starting.

Hornung scored five touchdowns that day and Green Bay won, 42-27.

That all changed when he settled down with Angela, Hornung said: “We got married in New Orleans. It was the best wedding they ever saw there. Pete Fountain and Al Hirt played.’

Asked what time of day he had married, he smiled knowingly: “Morning, but I didn’t know if it would last.”

He was referring to his famous claim: “Never get married in the morning. You never know who you might meet that night.”

Angela shook her head and laughed: “That old line again? I’ve heard them all, but you can’t believe everything you hear with him.”

So, as it turns out, Paul Hornung might have had a pretty good imagination, too.

About the Author