In her own words

Dayton librarian Minnie Althoff writes of being rescued at last after three days of privation in the downtown library: "By the end of the third day, rescue parties were seen, and word was sent around that those in unsafe buildings could be taken. Someone brought a box of grapefruit; the juice was refreshing, but by this time, my throat was too swollen to swallow. Toward evening, a militia man in a little boat said he was willing to take a few of us out, but at our own risk. In view of what we had been seeing, this sounded ominous, but anxiety for my people gave me courage. I was taken to my brother's house, there to learn of the safety of my parents, and re-united. Happy and grateful, we were ready to begin again — somewhere."

Althoff feared that bookbinder Theresa Walter had drowned in the lower floors of the library, but later learned she had escaped. The library lost 45,000 books, about half of its collection, but Althoff and her colleagues kept the losses from being far greater. Althoff died in 1962 at the age of 93.

To learn more about the Great Dayton Flood

Take the Great Dayton Flood Walk: Local historian Leon Bey leads a guided two-hour guided tour through downtown Dayton. For more information, visit gemcitycirclewalks.wetpaint.com or call 274-4749.

Museums

Dayton History: "The Great 1913 Flood" is the new permanent exhibit at Carillon Historical Park.

Miamisburg Historical Society: A flood exhibition is open from 1 t0 4 p.m. Wednesday and Saturday at the historic Market Square Building at 4 N. Main St, through June 9, when the city will host "A Tribute to the 1913 Flood" at 4 p.m. at Riverfront Park. Owners of small boats will launch their boat on the Great Miami River and take a 2.5-mile ride downriver.

New book:

"Drenched Uniforms and Battered Badges," by Stephen Grismer, recounts the role of Dayton police during the Great Flood of 1913 and how the police force emerged from the disaster. It describes the efforts of the 136 patrolmen who often acted on their own instincts in the first few days because they were in the field without lines of communication, transportation or supervision. Profits will be shared by Carillon Historical Park and Dayton Police History Foundation, Inc. Orders are being taken by e-mail: info@DaytonPoliceHistory.org or DPHFoundation@woh.rr.com.

Website commemorating the flood's centennial: http://www.1913flood.com: the most comprehensive site for historical information and photos.

Follow the series: 100 years after the Great Dayton Flood

Sunday: An overview of the causes and events surrounding the historic flood.

Monday: The Dayton Daily News follows the events of March 25 through the written accounts of survivors, including the story of 104-year-old Margaret Kender, now living in Florida.

Tuesday: Flood survivors face new dangers as gas explosions rock the city.

Wednesday: Survivors remain stranded in their attics and on their rooftops, not knowing when rescue might come. Snowfall is a blessing because it extinguishes fires throughout the city.

Today: The water starts to recede and some victims are able to leave their homes and begin the massive task of rebuilding.

TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THE FLOOD

Watch WHIO-TV chief meteorologist Jamie Simpson and reporter Jim Otte's special report on the Great Dayton Flood of 1913 at http://youtu.be/rFYH9xINZ_Y

One hundred years ago today, Daytonians emerged from their attics and began the long, arduous task of cleaning up, rebuilding and, most important of all, preventing the city from ever being flooded again.

On March 28, 1913, the waters had receded enough that most residents — half-frozen, half-starved — could safely return to the streets and search for missing loved ones.

A rescue boat arrived at the Mount Notre Dame convent at 6:30 a.m. delivering ham sandwiches prepared by the Marianist brothers. After breakfast, the 59 sisters assembled before the Blessed Sacrament to sing the Te Deum, the Christian hymn of thanksgiving.

It was a sentiment echoed all over the beleaguered city, but as the day wore on, Daytonians realized the full extent of the devastation, as well as the magnitude of the task ahead. The report from the Dayton Sanitation Department for the month after the flood tells the story: 133,600 wagon loads of debris removed; 13,991 houses and cellars cleaned and disinfected; 1,420 dead horses and 2,000 other dead animals removed. As Emma Grimes wrote to her sister, “Dayton is a mass of ruins, houses are piled on top of each other and you know everything people owned or had in their homes is scattered all over the streets.”

Thousands had been separated from husbands, wives, mothers and fathers, not knowing if their family members were alive or dead. Some would never be reunited.

Early national reports of the flood toll, such as the St. Louis Star headline, “6,800 Dead in Flood,” proved wildly exaggerated. It will never be known exactly how many died in Dayton; the official coroner’s report listed only 92, but some bodies were never recovered. The National Weather Service estimates the true number at somewhere between 98 and 123.

“When I look at the photographs I am amazed by the relatively small loss of life in Dayton compared to the destruction left by the flood,” said Mary Oliver, director of collections at Dayton History. “I think it was a combination of timing of the flood, coming in the morning instead of the overnight hours, and the willingness of people to try to rescue people, often strangers, stranded by the waters.”

Grace Hall left her handmade wedding dress behind when her fiance, Elwood Herbig, rescued her from the second-story window of her home in McPhersontown. Herbig went back to rescue more victims, and for several days Hall didn’t know if her fiance was alive or dead.

Reunited after the flood, the couple married March 31, with the bride wearing a red serge suit. But, as Grace wrote to a relative, “I guess I will be just as happy if I didn’t get to wear the beautiful dress I had made for occasion.”

Dayton’s legacy

That dress is now on display at the new permanent Dayton History exhibit, “The Great 1913 Flood,” at Carillon Historical Park. It’s part of the flood’s indelible legacy on our region — something that goes far beyond the high-water marks on downtown lamp posts, but speaks to the very soul of the city. “They did not let this keep them down,” Oliver said.

Virginia Burroughs of Celina said that her grandfather, Ray Murlin, was nearly killed by his own curiosity. Murlin lived with his wife Laura and their two children in the Ohmer Park neighborhood. “Their neighborhood was safe, but, being nosy, Grandpa decided to go into town and see what was happening,” Burroughs said. “He got on the last trolley into downtown, and of course didn’t get home until the trolleys started running again. Of course, Grandma was having a fit, since there was no way for her to know if he was dead or alive. But he was glad he had the story to tell afterwards.”

Some stories would be told and retold for generations. The flood had its heroes, even its instant celebrities.

Fireman Edward Doudna, the only member of the police and fire departments to lose his life, drowned while attempting to rescue a woman on West Third Street. She landed too hard in the boat and knocked him out of it.

The famous Dayton “flood twins,” Charles Otterbein Adams and Lois Viola Adams, became household names after the one-year-olds and their parents were rescued not once but twice from the raging waters. Charles Adams, a noted engineer, lectured frequently about the 1913 flood and became its most visible living link until his death Sept. 15, 2011, at the age of 99.

Just as remarkable as Daytonians’ response to the flood itself — the countless acts of bravery and selflessness — is what happened afterward. “The aftermath of the flood caused the entire Miami Valley to pull together,” observed Lee Smith of Beavercreek, whose father, Leon, then 4, narrowly missed being whipped out of his rescue boat as it moved under a neighbor’s clothesline.

The nuns at Notre Dame Academy opened a relief center only a day after their own rescue. “From Saturday morning until the following Tuesday, 78 persons were brought to the convent,” wrote Sister Helen Foran. “One woman stood on a roof from Tuesday until she was brought to us on Friday.”

In an era of racial discrimination, survivors reported that people of different races helped each other out. Nellie Neukom wrote to her daughter Lisetta about their African-American neighbors who shared fresh water and offered to teach them how to cook on coal stoves. “They are all very kind and good,” Neukom wrote. In 1988, retired schoolteacher Ella Lowry told the Dayton Daily News that her white neighbors helped her family. “People looked after each other,” she said.

The massive task of cleanup, which required 58 carloads of disinfectants, also was accomplished with a surprising speed that limited the spread of disease. NCR sent three steam storage locomotives into downtown on trolley tracks to haul away debris. The Dayton Bicycle Club spearheaded cleanup efforts including the removal of 1,420 dead horses from the city streets. Businesses re-opened almost immediately, inviting customers to navigate piles of debris to take advantage of “flood sales.”

Restoring normalcy

Dayton postmaster Charles Bieser was dismayed by the wreckage he found at the post office and his own downtown business, Everybody’s Office Outfitters. As his grandson, Dayton attorney Irvin Bieser, recounted, “Everybody’s was a cold, muddy, sticky, chaotic mess. All of the first-floor furniture, stationery, pens and display cases were covered in sticky mud and all merchandise was rendered totally useless. In the following days, open railroad boxcars were pulled onto the streetcar tracks running along the city streets, and merchants on both sides would shovel out their ruined merchandise for it to be hauled away to the dump.”

Some businesses, like the newly constructed Rike-Kumler department store, survived and even prospered well into the 20th century. Others, like the burnt-out Jewell Theatre on South Jefferson Street, never reopened. The Dayton Daily News, whose building at Fourth and Ludlow Streets had been submerged under 12 feet of water, borrowed a second-hand printing press, powered by a thresher, and published on the sidewalk on Ludlow Street. The March 28 edition carried the grim notice, “Dayton City Undertakers: Mr. John H. Patterson wants to meet with you this evening at 8 o’clock.”

One business, the Miamisburg Hamburger Wagon, was born as a result of the flood. The flood dumped 11 feet of water on the city and claimed six lives. Sherman “Cocky” Porter started making burgers in a skillet to feed the homeless and hungry during the long weeks of the refugee crisis. Today the Wagon is set up next to the Market Square building, where the “Cocky burger” remains a popular feature. “There is always a long line of people wanting to buy the burgers,” said Carol O’Connell of the Miamisburg Historical Society.

The true long-term impact on Miamisburg, O’Connell added, “is the sense of community that prevails today.”

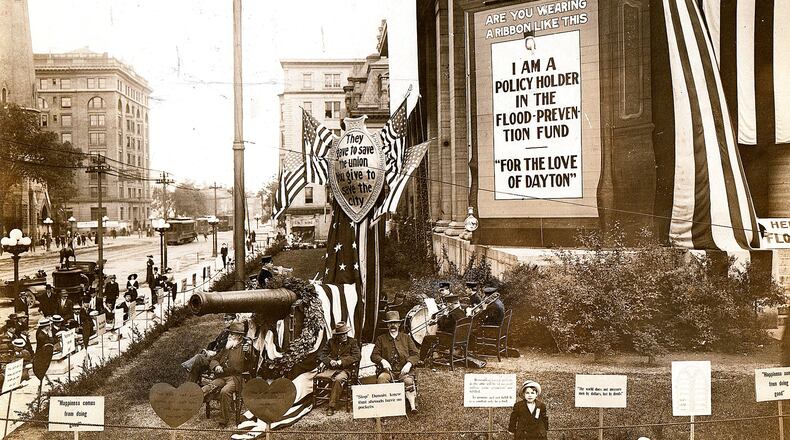

The slogan “Remember the Promises You Made in the Attic” inspired the stricken region to raise $2 million in private donations for the flood-prevention fund — a whopping $47 million in today’s dollars. “I think it was because a large portion of the city had just lost everything, or at least a whole lot, that the campaign was so successful,” Oliver said. “They did not want to go through that experience again and were willing, collectively, to do what it took to prevent it from ever happening again.”

Perhaps the most unlikely of the chief contributors was bordello operator Elizabeth Richter, who donated $1,500 to the flood-prevention fund — about $34,000 in today’s dollars — an amount that put her in league with the city’s most prominent families.

The flood prevention committee, formed on April 21, 1913, hired a visionary young engineer, Arthur Morgan, to create a preliminary flood prevention plan. New state legislation was written and passed in 1914 to permit work across jurisdictional boundaries, and the Miami Conservancy District was born.

‘Brillance and courage’

Sarah Jamison of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency in Cleveland said the regional approach was groundbreaking and a model for future public works. “It was the first of its kind in the country,” she said.

Prior to the 1913 flood, the levees near the business district were designed for a flood of 23 feet. Morgan’s innovative plan called for a series of dams, levees and flood protection plains designed to prevent floods more than 40 percent higher than the magnitude of the 1913 disaster (29 feet). People called it “Morgan’s Folly.”

“It wasn’t his folly; it was his brilliance and courage to say, ‘This will work,’” said Angela Manuszak, special projects coordinator for the Miami Conservancy District. “And it does work.”

Faith Morgan said that her grandfather was “a big-picture kind of guy” who was very pleased, throughout his long life, with what he accomplished in Dayton. She now runs the The Arthur Morgan Institute for Community Solutions in Yellow Springs.

Construction took place from 1918 to 1922, and family-friendly construction camps, complete with their own school districts, sprang up along the riverbanks from West Carrollton to Dayton. The flood prevention fund was used for the first few years of the construction project, until the bond issues raised enough funds to pay for the project. At that time, 83 percent of the funds raised in 1913 were returned to the contributors. No federal money was used either in the initial construction or in today’s system maintenance, which is paid through a special assessment on those that directly benefit.

To this day, the people in the Miami Valley should feel safe from future flooding, according to Kurt Rinehart, chief engineer for the Miami Conservancy District: “It’s a high degree of flood protection that very few have.”

Rinehart said the creation of the Conservancy District is emblematic of the Miami Valley’s spirit after the flood: “It immediately brought everyone together in a common can-do spirit that this is not going to defeat us, that we are Dayton, we are southwest Ohio, and we are going to survive.”

Concurred Oliver, “They had a phenomenal spirit. They came back stronger than ever. It was a defining moment in Dayton history.”

About the Author