Automation by the numbers

225,000 - Robots in use at U.S. factories

22,598 - Robots sold to North American companies in 2012

200,000 - U.S. and European business service jobs lost annually to automation

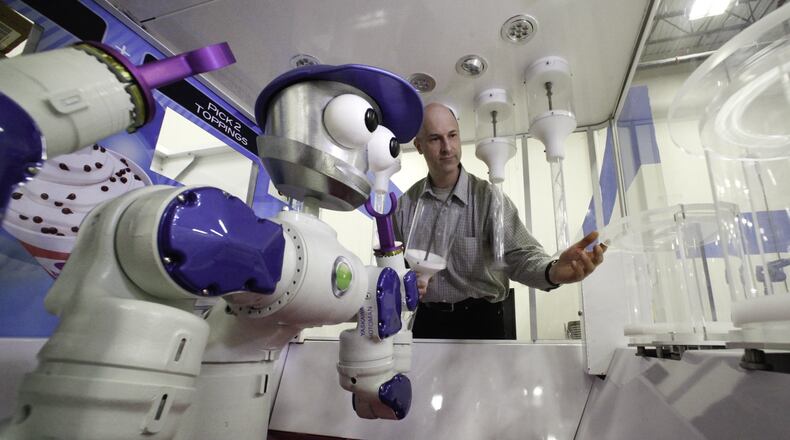

Visit the Great Wolf Lodge in Mason and you will find a robot that dispenses frozen yogurt just the way you like it.

Automation technology also allows machines to answer company telephones, make bank transactions, balance account ledgers, book travel and obtain tickets, check out retail purchases and read utility meters — all tasks previously performed by humans.

Robots and artificial intelligence are rapidly moving beyond the factory floor to new roles in service industries, which account for four out of five U.S. jobs. Many agricultural and manufacturing workers already have been replaced by machines that work faster and more efficiently, and other occupations, including some white-collar jobs, will soon follow, experts said.

“There is no question that some jobs are simply not going to be economically viable to be done by humans anymore,” said Raul Ordonez, an associate professor at the University of Dayton’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and director of the school’s Motoman Robotics Laboratory.

“The automation revolution is definitely happening; there is simply no way to stop it,” Ordonez said. “I think it will bring with it some pain in the sense that it will require all of us to adapt to it.”

Automation and other productivity improvements will result in the loss of 2.2 million business service jobs at U.S. and European companies between, 2006 and 2016, according to The Hackett Group, a Miami-based business consulting firm. Those factors are currently driving the elimination of around 200,000 jobs annually, according to the firm’s research.

But the automation revolution will benefit engineers and technicians who design, build, program and maintain the systems, Ordonez said. “The jobs that are gained will be higher-paying jobs,” he said.

The North American robotics market set records in 2012, according to the Robotic Industries Association, a Michigan-based industry trade group. A total of 22,598 robots valued at $1.48 billion were sold to North American companies last year, representing a nearly 17 percent increase from 2011.

The association estimates that some 225,000 robots are now in use at U.S. factories, placing the nation second only to Japan in robot use.

The Dayton-Cincinnati region is well positioned for the automated future because it is home to a number of robotics-related companies, as well as colleges and universities with robotics training programs, Ordonez said.

Miamisburg-based Yaskawa Motoman provides robots for the automotive manufacturing, heavy equipment construction, and material handling and packaging sectors. The company is looking for opportunities to deploy robotics in the service sector, and ultimately in consumers’ homes, said Tim DeRosett, Motoman’s director of marketing. Motoman employs more than 350 people locally.

Motoman recently partnered with South Carolina-based Robufusion to market automated kiosks featuring a dual-armed robot that dispenses frozen yogurt. Locally, the Reis and Irvy’s Frozen Yogurt Factory kiosks are installed at Great Wolf Lodge in Mason and COSI in Columbus. “People like the fact that no one is touching their food,” DeRosett said.

Robots are typically employed for tasks that are dull, degrading or dangerous, DeRosett said. They perform hard-to-fill jobs such as packing refrigerated products in a cold freezer, and reduce the risk of human repetitive-stress injuries.

“People are good at solving problems; they are not necessarily good at performing basic repetitive tasks over and over and over again,” DeRosett said. Automation frees up workers to take on other, more valuable roles, he said.

Interest in automation is at a record level as companies of all sizes are finding they can affordably and successfully apply robots, said Jeff Burnstein, Robotic Industries Association president.

“We are looking at innovative ways of using technology and that has always created new opportunities, new jobs that we haven’t even thought of yet, so certainly we are optimistic about the impact robots will have on job creation,” Burnstein said.

Experts said automation helps U.S. companies manufacture products at a cost that is globally competitive with countries such as China and India, where labor costs are rising. As a result, some manufacturing is returning to the U.S., helping companies to grow and ultimately create more jobs, DeRosett said.

Robot sales increased last year in non-manufacturing sectors such as the life science and pharmaceutical industries, which saw 3 percent growth, according to the RIA. Burnstein attributed some of that growth to automated pill packaging in pharmaceuticals plants, but robots also are being increasingly used for medical laboratory research.

“You can run automated testing 24 hours a day with robots doing all the handling of the specimens,” Burnstein said. The technology can accelerate the pace of research and also remove humans from a potentially hazardous environment, such as handling HIV-infected blood, he said.

Robots also can be used to address manual labor problems in industries such as the $17 billion nursery and greenhouse business. Boston-based startup Harvest Automation has developed robots that perform the physically demanding task of moving potted trees and shrubs around in plant nurseries.

“People will look at those tasks and say, ‘I wonder if we could figure out a way to have a robot do that.’ If the answer is yes, I think you will see more of that,” Burnstein said.

Google and Audi are developing robot-driven cars that could be commercially available within a few years, according to UD’s Ordonez. That technology ultimately could replace commercial truck drivers, who are limited to driving a certain number of hours under federal regulations designed to reduce accidents caused by driver fatigue.

“All those considerations that human drivers need to have are probably going to be out the window,” Ordonez said. “Those jobs, I can foresee them just going away and never coming back.”

About the Author