But just 20 days ago Dave Brittingham found himself in front of the polished, black granite wall that is the stirring centerpiece of the Vietnam Memorial. Alongside him was his 37-year-old son, Josh, an Iraq War veteran.

They had come to D.C. on an Honor Flight out of Dayton with 103 other veterans from the World War II, Korean and Vietnam war eras. Brittingham had agreed to the venture – in part, to placate his daughter, Sheila, who had signed him up — but soon realized something quite unexpected was happening:

“We were at the wall and I was telling Josh – ‘These names are here by the date they died; it’s like a book,’ — and then I turned and right there in front of me was Mike’s name!”

He was recounting that moment the other afternoon as he sat in the home dugout at the women’s softball field at Wright State, where he’s in his 14th season as a Raiders’ assistant coach.

As he thought about Sgt. Mike Stiglich, he grew quiet and finally shared his story:

“It was October 8, 1969. That’s when he went down. He’s the guy who trained me when I first got there. I’d flown 12 missions with him and there was a new kid on the flight, too. I’d flown three or four flights helping

train him.

“It happened just outside Phu Cat. They were hit and they lost an engine. There was a big storm and they weren’t able to hold it and crashed into a mountain.”

Stiglich was just 23.

“We lost three planes while I was there,” Brittingham said. “I knew guys on each.”

While the planes he was on sometimes got hit, he said he was lucky: “We had plenty of bullet holes in the wings, but we never got anything through the fuselage.”

After sharing stories with his son, Brittingham said he began to realize the Honor Flight experience was “a way of healing. I felt a sense of closure.”

Another Vietnam vet with a long association to Wright State athletics found himself especially moved on his Honor Flight, as well.

Jim Brown spent 26 years as WSU’s top assistant basketball coach and a season as the interim head coach. After moving on to coach at Northmont High School, he’s now back as the color commentator on Raiders’ radio broadcasts.

He’s remained loyal to the program, so much so that 12 days ago the team gave him one of the bulky championship rings it received for winning the Horizon League title last season.

At the impromptu ceremony near the end of practice, Coach Scott Nagy told his players about Browns’ WSU past. And had the young Raiders heard the rest of Brown’s story, they would have an even deeper appreciation of a guy they already respect.

After getting out of the University of Dayton — where he’d played freshman basketball for the Flyers and been in the ROTC program — he went straight into the Army and soon was on his way to Vietnam.

By then he already was married to Becky, today his wife of 51 years.

But he feared their future was in jeopardy when he got sent to Tay Ninh, a base just three miles from the Cambodian border. It was called “Rocket City” because it was targeted almost nightly by rockets and mortars launched from Cambodia.

Brown became the graves registration officer, which meant he was in charge of cleaning up the bodies of U.S. soldiers killed there, getting their effects together and then getting the slain servicemen to Saigon to be sent home.

As a prelude to Veterans Day today, Brown shared some stories while sitting at the kitchen table of his Beavercreek home the other day.

At times they left him tearful: “Yeah, I saw some terrible things there.”

He told of getting “this infantry guy, a West Point grad, a second lieutenant. He was the first officer that came through there – I was an officer, too – and it really bothered me.

“I can still see the young man lying there. His body was pristine. There was just a single bullet hole…through his heart.,. I still think about it.

“He had a whole life to live.”

“They all had lives to live,” said Becky, who was sitting nearby. “That’s what’s so sad about war.”

Tapes from home

Brown played basketball at Belmont High School in the mid-1960s and once at UD – whose basketball team he’d ardently followed since he was a kid – he was chosen as a freshman team walk-on from a pool of 95 guys who tried out.

Although Coach Tom Blackburn didn’t offer him a spot on the varsity the following year, his devotion to Flyers basketball didn’t wane and that would help him a few years later in Vietnam.

He remembers one night at Tay Ninh counting 238 rockets and mortars hitting around the base.

“Four of us officers lived in this little shack that had railroad ties on the roof,” he said with a shrug. “We told ourselves it could withstand a direct hit.”

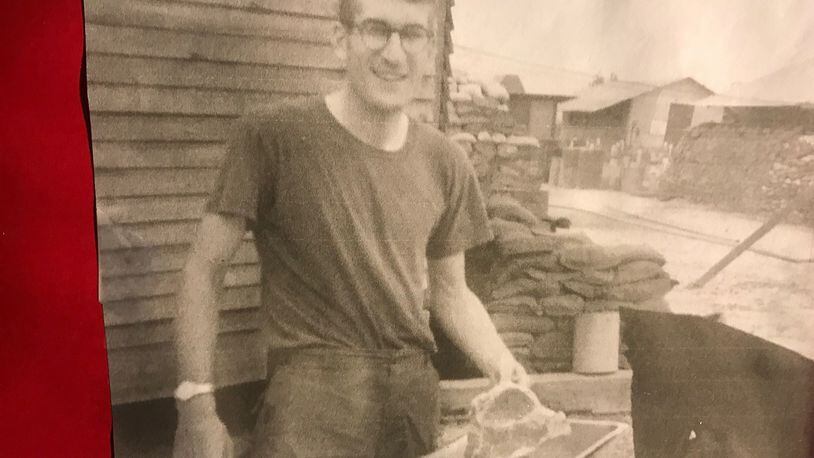

He pointed to a photo of him from Thanksgiving Day 1969. He’s cooking a T-bone steak, but instead he pointed to some quarters in the background: “See, we had sand bags all the way up to the top.”

While he also ran the laundry, the water and suds couldn’t scrub away the stain of death he dealt with in graves registration.

As he recalled various soldiers he prepared for the sad journey home – including eight guys on a helicopter that had crashed and burned everyone beyond recognition – he said the real relief came in the letters Becky wrote and a series of homemade tape recordings his dad, Floyd, sent him that year.

UD Arena had just opened and the Flyers – with Kenny May, George Janky, George Jackson and the Gottschall twins – would beat teams such as Louisville, DePaul and Marquette and make the NCAA Tournament.

His dad took a tape recorder to his seat high in the arena, brought along a transistor radio and recorded the broadcast and the cheers of the crowd while adding his own comments at the end of each session. He’d then send those tapes to his son.

“I’d lay in that bunker and listen to those games and the other guys thought I was nuts,” Brown once told me.

“I was a huge fan. I lived and died with the Flyers every game. And I can’t tell you how much those tapes meant to me, what they did for me. It was like I was right there at the games. They made me feel happy and safe and they reminded me of the place I wanted to get back to.”

‘Life isn’t always what you think it is’

Brittingham, who initially lived in Dayton, ended up with his mom in Valparaiso, Ind. after his parents divorced. After graduation he returned here to get to know his dad and find a factory job.

Soon though he went to the Air Force recruiting office in Xenia, signed up and after tech school in Biloxi, Miss., he said he went to the island of Crete in the Mediterranean.

“I guess I can talk about it now, they declassified it finally,” he said. “I was a radio operator and I was copying all the embassies in the Mideast.

“That’s when they came to a few of us about a special unit they were forming. I was one of two guys who took it.”

He was sent back to the States for more training – everything from cryptology to survival school – and got more jungle training in the Philippines.

A radio operator assigned to an EC-47, he was charged with locating low radio signals used by the enemy and then, depending on where they were, troops or airstrikes were called in.

He said he was told they were the first plane to fly into Cambodia and he said they flew regularly into Laos.

The EC-47s – which he said flew low and slow – were often targeted and he has a few harrowing tales, including one about a guy he was in test school with – Danny Russell – whose plane they were about to relieve when it was shot down in Laos.

He tells how they were surrounded by Vietcong, but a helicopter was able to come in and rescue Russell and four of the others, only to then be shot down itself. A second rescue effort got the survivors out and destroyed the downed copter so it didn’t fall into enemy hands.

“Back then we believed we were going there to help our country fight communist intervention,” he said.” Later, after some of the things you saw go on there, you realized it was political and about economics.

“I learned life isn’t always what you think it is, but I also learned about loyalty at a deeper level than you ever had with your school or anything like that.”

After he got home, he worked 36 years at General Motors – doing everything from line work to chemical dependency counseling – raised a family and stayed active in sports.

He’s with his fifth Raiders head coach – former UD standout Laura Matthews — and still relishes the job because he said being around the players keeps him young and enables him to stay close to the game he loves.

‘One of the greatest days of my life’

Neither Brittingham nor Brown experienced much fanfare when they came home from Vietnam.

Brown – who arrived back in San Francisco in February of 1970 – said he took an exit route designated for officers and was greeted with a big wall mural of Uncle Sam that simply proclaimed: “Thank you for your service.”

When he landed in Dayton, only Becky was waiting for him.

Instead of embrace, Brittingham got confrontation.

“I was in the Seattle airport – in uniform so I could fly standby – and a lady walked up and spit on me,” he said. “That was my welcome home. A lot of people just didn’t like you if they found out you were in Vietnam.”

While both men went on to forge their own lives, Brown had a unique opportunity first introduced to him in a letter he got in Vietnam from his old Belmont coach, John Ross, who was launching the WSU basketball program.

He wanted him to be his assistant coach.

And a week after he’d gotten back to Dayton, Brown was out recruiting Jimmy Minch and Dave Magil both who became Raiders.

Over the next 27 years — working under Ross, Marcus Jackson and Ralph Underhill, with whom he helped coach the Raiders to the NCAA Division II national title in 1983 — he had a hand in recruiting every player who came to WSU.

When Underhill was let go right before the 1996-97 season, Brown took over for a year.

Brittingham has spent more than 40 years as a player and coach in the area – guiding the Xenia High baseball team, the Miami Valley Xpress travelling fast pitch team and now WSU – and in 2012 was enshrined in the Ohio Amateur Softball Association Hall of Honor.

Neither guy knew quite what to expect when he joined an Honor Flight.

“It ended up one of the greatest days of my life, no question about it,” a tearful Brown said of his April 2017 trip. “The way you were treated, it was phenomenal.”

In Washington, D.C. — where a large Green Day celebration was in full swing — he said people continually came up and thanked the vets for their service.

He told the story of a 92-year-old World War II veteran in a wheelchair who was moved by his son to the Ohio pillar of WWII memorial for a photo, but instead drew a crowd of 100 strangers who wanted to thank him.

On the flight home, Brown said each veteran was given a stack of letters secretly mailed to them by family, friends and even strangers.

The biggest surprise came when the group got back into the Dayton airport late that night.

“There were people 10 deep lining the corridors,” Brown said with glistening eyes.

“It was like a parade.” said Becky, who was there with son Anthony, two daughters-in-law and four grandkids. They held signs and cheered, as did many others.

“I’m not sure what was happening,” Brown admitted. “I was crying the whole time”.

Brittingham was moved by the reception as well, but he especially cherished the time he spent sharing experiences with his son.

When Josh was sent to Iraq, Brittingham said: “I wanted them to let him come home and send me in his place. I knew some of what he’d face.”

Both men talked of what the Honor Flights did for them.

Brown felt pride, Brittingham felt healing and both men smiled – especially Brown when he read a letter from his granddaughter, Kinsley, then a Springboro Elementary fourth grader, who cut to the chase:

“Thank you for your hard work and for protecting us.

“I’m glad you are still alive.”

About the Author